Stuck in the Bottle: Vodka in Russia 1863-1925

Andreasen, Bryce David

University of Lethbridge Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada

Abstract

This paper looks at how Vodka has played a role in Russian society, specifically in the years immediately before and after the Revolution which toppled the monarchy of Tsar Nicholas II. It looks at Vodka and how it related to a number of different aspects of Russia such as: Social life, the workplace, the military, government, and the Prohibition and its subsequent end. This paper looks at these different aspects of society and how Vodka became ingrained within Russian society, and how even the mighty Bolshevik party could not eliminate vodka from the society.

Citation

Stuck in the Bottle: Vodka in Russia 1863-1925. Andreasen, Bryce David . Lethbridge Undergraduate Research Journal. Volume 1 Number 1. 2006.

“Drinking is the joy of the Rusi, we cannot do without it.”1 -Prince Vladimir 10th Century AD

No quote better sums up the importance of alcohol to the Russian people. As Boris Segal says “His statement survives as a virtual slogan for Russian behavior through the ages.”2 Alcohol, more specifically Vodka, has been as important to Russia as hockey is to Canada ever since the sixteenth century A.D. It is the general consensus that Vodka became popular in Russia around the time when Ivan IV, or as he is more affectionately known, Ivan the Terrible was in power. It was first introduced to Russia sometime around the fourteenth century, but it was not popular until later in the sixteenth century. The Russians referred to this particular type of alcohol as vodka, which means “little water”.3 Vodka permeated every level of society from children to peasants to the military to the politicians to the Tsar himself. There was no doubt that Vodka played an important role in the lives of Russians. According to Stephen White “vodka was the ‘single most important item in the peasantry's festive diet'; it was a ‘basic ingredient of all celebrations' and a ‘sort of seal on ceremonials'.”.4 White also says that “nearly 90 per cent of all drink was consumed in the form of vodka.”5 This statement shows that even though Russians had the option to drink beer or wine, the they preferred the taste of vodka. This paper will look at how vodka affected Russian life from the 1860s until the end of prohibition in 1925. It will show that if there is one thing in Russian life that is constant it is the love of vodka by the Russians. Even one of the most powerful and brutal regimes, the Bolsheviks, could not fully remove Vodka from their lives.

Vodka and Social Custom

The most important reason that vodka was able to remain a large part of Russian life is because it was embedded into Russian social life. Vodka was the popular drink at almost all major events within Russian life. It was used at church ceremonies, festivals, weddings, political events, business transactions and finally the pomoch. Drinking vodka was the customary (bytovoi) thing to do at any event in a Russians life. Vodka was also believed to be a medicine as well as an anesthetic.6 Thus it is clear that vodka had a variety of uses within Russian life. Whether a family member was sick or celebrating, a drink of vodka would help. Church events no doubt played the largest part in drinking. According to Herlihy, the peasants in Ufa Guberniia said “Orthodox Feasts days claimed ‘more than one-third' of the year”.7 Sometimes the party would carry on for days after the feast which led to even more drinking. The extra days of celebration were referred to as podgvozdki.8 It almost seems as if the word vodka has been incorporated in this word.. vozdki, it may just be a strange coincidence though. Festivals also were an important time to drink Vodka. In Smith's book, Bread and Salt, he claims that vodka was drunk during the festivals because it “has primarily a psychological significance, a sort of compensation for the absence of entertainments”.9 I could agree with this because as the people at the festival drink more it is without a doubt that they would probably become more entertaining. However, I believe the main problem in this form of ‘entertainment' is that they would drink to excess as many Russians usually did at festivals.

Figure 1: Drunken revelers on a church holiday. Couresy of the Hoover Institution Library and Archives. 10

Weddings also showed how peasants would consume great quantities of vodka, and spend large amounts of money on one occasion. According to Patricia Herlihy “the bridegroom commonly provided six to eight vedros of vodka (approximately seventy-five to a hundred liters), all of which was drunk before the wedding. At the wedding itself the bride's family might spend as much as two hundred rubles on Vodka.”11 This was an immense amount of money to spend on one occasion, especially for a peasant family, let alone a poorer peasant family. This only goes to show how important vodka was to the Russian peasantry.

The pomoch (help) is one of the major events in the countryside that almost inevitably required the use of vodka. The pomoch is a call for help when a peasant may need extra workers for pretty much anything. According to Smith, the pomoch was “A househould which had to get an urgent task done, for which it did not have enough labour, would hold a work-party, inviting friends and relatives to help them with their work, in return for a meal and some vodka.”.12 Patricia Herlihy gives a similar view of the pomoch except that it was more about “neighborliness, friendliness, and hospitality—even charity.”13 Pomoch was not paid work in the sense that the people who did come to help were not paid with money. Instead peasants were paid with the hospitality of the family that needed help. The workers were without a doubt given food as well as vodka. The social consequences of this type of work were quite obvious and far-reaching. It was obviously cheaper for the person who needed help to pay with vodka instead of currency. According to I. Lopatin (a peasant) “the village youth loved pomoch', but it was also the occasion by which many young men were introduced to heavy drinking.”.14 Inevitably the pomoch turned more into a drunken spectacle than a productive occasion. Herlihy and Smith both agree on this point. Herlihy says by the end of the day most of the workers were either passed out at the table or else they would fall over dead drunk on the way home.15 Smith gives evidence of this from a village priest who witnessed the pomoch parties (inevitably they ended up being a party) said this about them “The local people go to work-parties, it seems, less to help their neighbours than to enjoy themselves and get drunk.”16 This makes it seem more like a social gathering rather than a work group. Getting drunk and being fed by the host seems to be the most important aspect of the pomoch. Indeed it was, according to Herlihy who gives a warning to the host “Woe to the host whose vodka was poor or whose meal was skimpy! His next call for help would fall on deaf ears among the villagers.”17 Clearly pomoch was more a social event than anything else. Work was a distant second when a pomoch was called.

Vodka in the Military

The Russian military was another area of major concern where Vodka played an important role. Vodka was used as a way for the soldiers to celebrate, as well as a way to keep them happy. Concern about drinking in the military started relatively early compared to the other temperance movements. As early as the 1870s some commanding officers were talking about the ill effects of alcohol. This concern was not widely shared amongst the rest of the army. P.E. Keppen and General Konderovskii were among the first to express their concern. The main concern was over the “vodka ration” which was given to sailors and soldiers regularly.18 Dr. P. Suvarov was against the “vodka ration”. He believed that by withholding the ration “troop morale, comportment, discipline, and performance in the action against Khiva in 1873 were all enhanced.”.19 Suvarov was not alone in his view that alcohol was decreasing the fitness level of the Russian army. Two commanding officers, Butovskii and T.D.(a pseudonym) both expressed their concern on the effects of alcohol. Butovskii claimed that vodka had negative influences of troop behavior such as “smuggling of vodka into the barracks, its secret consumption, and particularly the behavior which followed it: drunkenness, disorder, and crimes and misdemeanors committed by drunken soldiers.”.20 Butovskii also feared that this negative aspect of drinking would soon contaminate the new recruits, and in many cases this was true. The process of turning new recruits into alcoholics and drunks was inescapable due to the social aspect of drinking. It was custom to drink with your friends and could be considered insulting if you did not. Butovskii gives evidence of this by looking at a group from the1878 draft that had finished service in 1883.21 According to these statistics upon entering service 43% did not take their “vodka ration”, and 10% drank more than the ration. A year later, 17% were refusing the vodka ration and 27% were now drinking the ration and extra on the side. By 1883 the numbers had drastically changed towards those drinking more than the ration.22 Butovskii claims that only 7% were not drinking the ration and “fully half drank “on the side”“.23 This radical increase in excessive drinking no doubt was due to the fact that there was pressure on the newly recruited to take part in the social activity of drinking. The example that Snow gives is of the drinkers calling the non-drinkers names such as “old woman” or “dawdler”.24 Snow observes “Nothing could be so offensive to a soldier as ridicule of his military prowess”.25 While this was one of the main problems, another concern was the number of times the rations were doled out. The rations were usually given when the “commanders wished to stimulate or reward the troops” or when there were holidays.26 The Navy was particularly bad with the vodka rations because it was believed that vodka had “energizing and warming properties.”27 Since the Navy inevitably had to deal with cold weather it was only natural that more rations were given to them than soldiers in the army. With peer pressure, customs and the numerous holidays that dotted the Russian calendar, it was no doubt that many of these men would soon learn to drink. Butovskii comments on how the drinking problem was similar to smoking cigarettes. He basically says that once you have had a few you begin to get used to the feeling and this is how many young recruits got hooked on Vodka.

The Temperance movement in the military finally came to a head in the 1890s when problems with alcoholism became more popular in the public. There was a very large resistance within the military to remove alcohol because they believed that it kept the soldiers happy as well it had medicinal effects. The creation of the Russian Society for the Protection of Public Health spawned a commission that was to look into the problem of alcoholism. It was called the Commission for Combating Alcoholism.28 This was a thorn in the military's side because some people wanted to eliminate alcohol completely from the military. M.N. Nizhegorodtsev, a psychiatrist headed one such sub-commission, which was for the “total elimination” of alcohol within the military.29 He wanted to eliminate all alcohol in the camps and barracks and instead provide the soldiers with a daily tea allowance. He also suggested that they needed to keep the soldiers busy during down time and could accomplish this by setting up “recreational activities for men of the lower ranks.”30 The main problem with these reforms is that vodka was a mainstay of life in Russia whether you were in the military or not; as well, it had been popular in the military for a long time because it was a way for the men to meet, talk and to join in comradery. This commission also seemed to think that the drinking problem was mainly within the lower ranks. Another doctor who looked at the problem of drinking was P.V. Putilov. He looked at the injuries and deaths that were probably linked to alcohol, but were not reported as such. According to Putilov “he estimated that alcohol poisoning was the true cause of 75 percent of all the ailments of soldiers who entered medical establishments for treatment between 1890 and 1896 and between 10 percent to 44 percent of all deaths”.31 If Putilov's figures are accurate it would definitely suggest that alcohol played a devastating role in the military. The military's responses to these accusations were slim to none. They in essence blew off the suggestion of Nizhegorodtsev and Putilov, and suggested instead to print off pamphlets that warned of the dangers of alcohol.32 They also argued in support of the Navy, “naval life sometimes called for levels of energy that could only be gained by a glass of vodka.”.33

The major blow that affected the military, without a doubt, was the complete incompetence that was witnessed in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-1905. It is widely believed that alcohol was one of the major reasons that the war was a disaster. There were immense amounts of alcohol sent to the war, one example is from a article in 1910 that talks about the subsistence of the Russian Army. The report claims “the official plan of subsistence for August 1904 contemplated 300,000 poods of vodka for an army of 400,000 men for eight months and an additional 255,000 poods for the following year.”.34 A pood is equal to 16 kilograms; this amounts to 4.8 million kilograms of vodka.35 That is about 12 kilograms of vodka for each of the 400,000 soldiers. It is not hard to understand that many of the soldiers may have been too drunk to fight. One account from the war that Chelysev used to promote temperance in the military says “the Japanese found several thousand Russian soldiers so dead drunk that they were able to bayonet them like so many pigs.”36 This account seems very far-fetched, but another account from Dr. Veresaev who was a field physician claimed to have seen “masses of aimlessly wandering soldiers, red-eyed from alcohol, dust and exhaustion, surrounded an official from the quartermaster's office who ladled vodka from a huge barrel to anyone who wanted it.”37 After this catastrophic incident the military decided instead that they should give out light wine or beer instead of Vodka.38 This put an end to the temperance debate in the military, at least until World War One when the government decided that prohibition was the best solution during mobilization. This eventually led to the complete “ban on sales of spirits, wine and vodkas”39 on August 22, 1914, which would carry through the duration of the war. By September 29, 1916, the distilling of anything beer, wine, or vodka was completely prohibited.

Vodka in the Workplace

The workplace of many Russians was also a place where vodka played an important socializing role. In the years before the revolution the tradition of prival'naia40 , a welcoming ceremony, was used to welcome a new worker to his job.41 New workers would treat the other workers with vodka and snacks. It was a way for the new worker to get acquainted with his fellow workers, but it also had a more important role. By treating the other workers to the prival'naia the new worker would in turn receive training for his new job. Another instance where a worker was expected to provide vodka was when he received a promotion. In Patricia Herlihy's article Joy of the Rus' she says “It was an unwritten rule among Russian factory workers that a newly hired or newly promoted42 worker should treat his fellow workers to drinks.”43 If the new worker did not treat the other workers to drink and snacks, there was a good chance that he would not be able to acquire the necessary skills to do his job. The worker could also be ostracized at work by name calling, teasing, insults or social isolation.44 It was in the workers best interest to buy his comrades a drink. This tradition was not a small expenditure for a worker. According to Laura Phillips it would cost “two to three rubles” but on some occasions workers had “sacrificed eight rubles”.45 Two or three rubles often meant a couple of days of wages would be spent on one drinking bout. By the 1920s when the Communists had almost complete control of the country, drinking practices in the workplace had changed. The Soviet believed “there was “no place” for alcohol in the factory.”46 They produced literature that told the workers of the detrimental effects that alcohol had in the workplace. Drinking in the workplace led to accidents, lower productivity and a general reduction of productivity in the workplace. The Soviets would place guards in an attempt to thwart alcohol coming into the workplace, as well as make sure laborers were not intoxicated when they showed up.47 This was particulary important during the years when the soviets were in control as productivity was an important aspect of their philosophy. The attempts by the Soviets did not prove very effective, although some drinking habits did change. Laborers continued to bring vodka into the workplace, sneaking it past the guards and hiding it in various places around the factory.

The tradition of prival'naia was one of the big changes in the factory during the soviet period. According to Phillips, this tradition slowly became less popular because of the way that workers were hired. Prior to the revolution she claims that workers were “hired upon the recommendation of an acquaintance, and a newcomer's provision of prival'naia was one way to clear his debt.”48 After the revolution this changed because the hiring “became a more impersonal process” because of trade unions. People no longer had a reason to treat the other workers because they did not have to pay them back for getting them a job. There were also trade schools set up by the trade unions, and eliminated the need for other workers to train a new recruit.49 Even though these changes drastically cut down on the occurrence of prival'naia, some people still practiced it.

The Politics of Vodka

Alcoholism and drunkenness problem appeared again in the autumn of 1907 during the Third State Duma. M.D. Chleysev, a member of the Octobrists, was the main pusher of trying to curb the sale of vodka in the country. According to Hutchinson his only reason for joining the Octobrists was because they were numerically superior. His solution to the problem was far more radical than any of the parties in the Duma were willing to go. Chelysev wanted the Duma to “declare alcohol a poison, to ban its manufacture” as well “order the Ministry of Finance to compensate all those who had suffered from its effects.”50 This would put a severe crimp in the tsar's pocket because it would eliminate around third of the countries income, further it would have to compensate people who had ‘suffered from its effects'.51 The other side of the argument came from a group of scientists in the Commission for the Study of the Alcohol Problem.52 The scientist's gave little support to Chelysev. The scientist's solution to the alcohol problem was targeted at economic and social reform instead of just eliminating alcohol completely. According to Dr. D.A. Dril' “vindictive measures were at best pointless and at worst dangerous because they could well exacerbate existing problems.”.53 A third group was involved in this discussion as well. These were the Octobrist's who wanted to solve the alcohol problem, but they did not want to lose the income from the alcohol trade. While all three groups could agree that Russia did have a drinking problem, the solutions seemed to be on all ends of the spectrum. The radicals wanted to eliminate the problem completely. The Octobrists wanted to solve the problem, but not at the expense of the revenue. The Scientists wanted to change to population through education, and increasing the social status of the people. The alcohol problem was a major dilemma according to Hutchinson because “it could be made to touch anything and everything: agriculture and rural life, industry and urban life, the family, the position of women, education, public health, crime, prostitution, and even national defence.”54 Because the alcohol question had such far reaching effects the discussion of how to deal with it never got any farther than talk. None of the sides wanted to give up power to the other. The ultimate determining factor in the prohibition in 1914 was probably the start of the Great War and the fear that in would be another Russo-Japan catastrophe.

Prohibition in Russia and its Effects

The prohibition in Russia was a severe setback economically for the tsarist government as well for the Bolsheviks after the revolution, producing a great amount of anger amongst the Russian populations. The economic impact was by far the greatest on the Tsarist government. Vodka production was a great source of income for the tsarist government during the 1800s. According to David Christian's article “government revenues from vodka were the major single source of government revenue, accounting on average for 30% of all ordinary revenues.”55 The fact that alcohol sales from vodka made up 30% of the ordinary revenues hints toward its popularity among the people. In the years preceding the prohibition, from 1910-1913 liquor revenues ranged from 27.9 to 29.2 percent of total government revenues.56 In 1894 the government introduced a total state monopoly on the liquor trade. This drastically increased the amount of revenue that the government would receive now that it alone controlled the sale and distillation of vodka. From this point until 1913 the amount of revenue that the government received from liquor sales was incredible. Before 1894 liquor revenues had been around 260 million silver rubles and had been fairly constant for the last ten years or so.57 After 1894 the amount of revenue from alcohol went from 297 million rubles in 1894 to 953 million rubles in 1913.58 The vodka that the Tsar produced was cheap, strong and of good quality and was the only product available. It is no wonder the Russian people believed that the tsar was becoming rich off the ruin of the people.

Figure 2: Cartoons showing the Tsar making a living off the drunken people (1918) 59

When the government decided to ban sales of alcohol before the Great War it decimated large amounts of income that the government needed to wage the war. Around one third of their income vanished overnight.60 Why did the government make a decision on the eve of war that would cut their income by one third? One reason I believe is because the government feared another disaster like the Russo-Japanese War. They did not want their army to be inebriated and face an utter disaster yet again. The second reason may be that the government felt an obligation to not make money off the suffering its people. In January 1914 Nicholas II appointed a new minister of finance by the name of P.L. Bark.61 Bark felt that “ ‘the welfare of the Treasury should not be made dependant on the ruin of the moral and economic forces of a great number of Our loyal subjects'.”62 It is strange that the Tsarist government had now become worried about making money off of the peasants when it had not been a problem for the last few hundred years. The 1905 revolution might have made them more cautious about what they were doing.

The prohibition also had another profound effect on life in Russia besides the economic catastrophe. The prohibition in fact spurred on another type of economy; and the government was not going to reap the benefits this time. The production of bootleg alcohol and samogon (Illegal, home brew alcohol) became widely popular during this period. Bootleg alcohol was available in many forms, “polish, varnish, denatured alcohol” as well as cologne.63 One of the cologne products that was available was known as “Eau-de-cologne No. 3”64 It was clear that the people were going to drink anything, no matter what it was or how horrible it must have tasted. Another statistic that shows how much the Russians truly loved to drink comes from the pharmacies that were still allowed to sell alcohol for “industrial or medical purposes”.65 It was reported that pharmacies alone were selling “between 10 and 20 times” the amount of alcohol during the war.66 It was clear that alcohol was an important aspect of Russian life.

Samogon was by far the most popular way for the population to obtain alcohol. Samogon was made in illegal stills, usually by the peasants, and then either sold or used for their own consumption. Soon after the prohibition started in 1914 the Ministry of Agriculture found 1,825 illegal distilleries.67 By 1915 the number had risen and “The Excise Department found 5,707 cases of illicit distilling”.68 The number of stills, at least the ones that they found, had multiplied three times within a year.

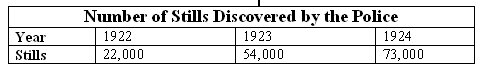

Table 169

Data from later years shows how quickly the use of illegal stills had grown to just before the end of the prohibition. Even within the three years between 1922 and 1924 the number of illegal stills more than tripled. The reason that it became widely popular to produce samogon was because it was cheap to make, because the peasants already had the necessary material, as well it was widely available because many households were brewing their own vodka. Of course there was a lot of variation in quality, from completely horrible to almost perfect. It was no match for the vodka that the government had produced before the prohibition.

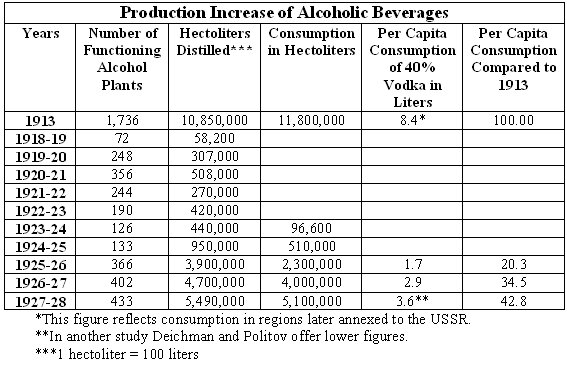

Table 270

The above table shows both the production and consumption of alcohol in Russia from 1913 to 1928. It shows both how the prohibition affected production as well as how it affected the consumption. In 1913 just before the prohibition started the production of Vodka was enormous. There are no figures between 1914 and 1918 because there was supposed to be a prohibition, although vodka was still consumed in large quantities during this time through the use of samogon. After prohibition the per capita consumption was on the rise again and by 1927/28 it had reached a level that was 43% of what it had been before prohibition. I believe these numbers only represent the government's figures and so may not have added in illegal distillery numbers.

End of Prohibition

While the Communist government was against alcohol it would have a tough time eliminating it from Russia. Trotsky said “'The petty bourgeoisie, in order to defeat the workers, soldiers, and peasants, would combine with the devil himself!’”.71 He then remarked “ ‘No drinking, comrades! No one must be on the streets after eight in the evening, except the regular guards. All places suspected of having stores of liquor should be searched, and the liquor destroyed. No mercy to the sellers of liquor... ’”.72 Trotsky is equating alcohol with the bourgeoisie, the enemy of communism as well as the devil. This is out of character because, as stated in the Manifesto of the Communist Party by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels “Communism abolishes eternal truths, it abolishes all religion... ” as such, Trotsky being a party member should not be referencing the devil.73 With bootlegging and samogon production on the rise the government had a couple of options. They could continue the prohibition and continue to spend money on fighting the illegal distillers, or they could end the prohibition and create revenue from its sale. By the end of 1919 the Communist government had legalized the sale of grape wine, with a limit of 12% alcohol. By the end of the civil war further steps were taken to end the prohibition.

August 1921: Sale of wine legalized 1922: Sale of beer legalized January 1923: Sale of drinks no stronger than 20% legalized December 1924: Limit on alcoholic drinks raised to 30% August 1925: Sales of 40% vodka legalized from 1 October 74

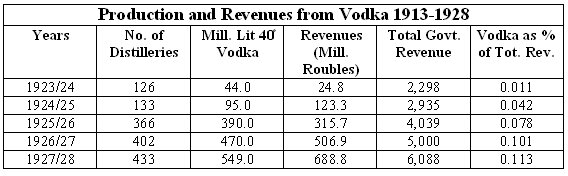

Table 375

It is clear from table 2 and 376 that by slowly getting rid of the prohibition the government could see consumption and revenues increasing, especially after the sale of 40% vodka was legalized. The jump is startling. Legalizing beer and wine sales did very little to increase revenues but the same year that 40% vodka was legalized the profits that the government saw increased by 2.5 times. Consumption increased by 4.5 times. These numbers would continue to increase and by 1927-28 just three years after the sale of 40% vodka was legalized their profits would multiply by six. It was definitely in their best interest economically to get rid of the prohibition and sell vodka once again, even if at the expense of the people.

Conclusion

While it may seem like all parts of society in Russia turned to Vodka for comfort, sociability or plain fun, it did not permeate all levels of Russian society. Some groups that did not drink or drank more moderately included the Jewish, Old Believers, other schismatics and of course the Muslim population.77 These populations tended to drink sparingly, or not at all. The main reason that Prince Vladimir chose Christianity over Islam was because they wanted to drink. It is also important to remember that the Russian people did not all start out as avid drinkers. Even in the military according to Butovskii 43% of new recruits did not take their vodka ration during their first year in the military.78 Unfortunately as time went on this statistic would reverse and nearly half of them would be drinking their ration plus more on the side. This phenomenon was largely due to the peer pressure exerted by his fellow, and usually senior officers, of drinking with your comrades. Young drinkers were usually introduced to vodka at social functions, such as pomoch.

In conclusion vodka was the lifeblood of the Russian people. It has been integrated into every part of Russian life from the politicians to the military to the poorest of peasants since the fourteenth century. It permeated life in play and work. Even the military, a bastion of control and order, was unable to take control of the overpowering affects of alcohol. When the prohibition tried to put an end to Russia's love of vodka the people found a way to produce and consume it. The only major effects the prohibition had on Russia was that it severely crippled the governments profits, from which it would never fully recover. The production of samogon made sure that when the government did try to regain control of the alcohol trade it was a failure. The peasants had learnt how to make their own alcohol and no longer needed the government to produce it for them. As Prince Vladimir said in the tenth century “Drinking is the joy of the Rusi, we cannot do without it.”, and this quote still held true until the end of the prohibition.79

Endnotes

1. Segal, Boris M. The Drunken Society Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in the Soviet Union A Comparative Study. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1990. p. 2

2. ibid

3. Herlihy, Patricia. “Joy of the Rus': Rites and Rituals of Russian Drinking”. In Russian Review. Vol. 50, No. 2 (Apr. 1991) pgs. 131-147. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=00360341%28199104%2950%3A2%3C131%3AJOTRRA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-O p.131

4. White, Stephen. Russia goes dry : alcohol, state and society. Cambridge [England] : Cambridge University Press, 1996. p.3

5. ibid p.10

6. Smith, R.E.F., et. al. Bread and Salt A social and economic history of food and drink in Russia. 1st ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984. p.316

7. Herlihy, Patricia. “Joy of the Rus': Rites and Rituals of Russian Drinking” p.134

8. ibid

9. ibid p.317

10. Herlihy, Patricia. The alcoholic empire: vodka & politics in late Imperial Russia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. Photo Gallery section, no page number

11. Herlihy, Patricia. “Joy of the Rus': Rites and Rituals of Russian Drinking” p.135

12. Smith, R.E.F., et. al. Bread and Salt A social and economic history of food and drink in Russia. p.319

13. Herlihy, Patricia. “Joy of the Rus': Rites and Rituals of Russian Drinking” p.137

14. ibid p.139

15. ibid p.140

16. Smith, R.E.F., et. al. Bread and Salt A social and economic history of food and drink in Russia. p.321

17. Herlihy, Patricia. “Joy of the Rus': Rites and Rituals of Russian Drinking” p.139

18. Snow, George E. “ALCOHOLISM IN THE RUSSIAN MILITARY: THE PUBLIC SPHERE AND THE TEMPERANCE DISCOURSE, 1883-1917.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas [Germany] 1997 45(3): p.418

19. ibid

20. ibid p.419

21. Snow, George E. “ALCOHOLISM IN THE RUSSIAN MILITARY: THE PUBLIC SPHERE AND THE TEMPERANCE DISCOURSE, 1883-1917” p.419

22. ibid p.420

23. ibid

24. ibid p.421

25. ibid

26. ibid

27. ibid p.422

28. Snow, George E. “ALCOHOLISM IN THE RUSSIAN MILITARY: THE PUBLIC SPHERE AND THE TEMPERANCE DISCOURSE, 1883-1917 p.423

29. ibid p.424

30. ibid

31. Snow, George E. “ALCOHOLISM IN THE RUSSIAN MILITARY: THE PUBLIC SPHERE AND THE TEMPERANCE DISCOURSE, 1883-1917.” p.425

32. ibid p.425

33. ibid p.425

34. ibid p.427

35. “Weight Conversion” Speck Design web space. Visited: March 19, 2004 http://www.speckdesign.com/Tweight.html.

36. Snow, George E. “ALCOHOLISM IN THE RUSSIAN MILITARY: THE PUBLIC SPHERE AND THE TEMPERANCE DISCOURSE, 1883-1917.” p.427

37. ibid pgs.427-428

38. ibid pg.428

39. Christian, David. “PROHIBITION IN RUSSIA 1914-1925.” Australian Slavonic and East European Studies [Australia] 1995 9(2): 89-118 p.92

40. This is the term that was used in St. Petersburg, but it was also known under a variety of different names. According to Patricia Herlihy it was called prival'noe.

41. Phillips, Laura L. Bolsheviks and the Bottle Drink and Worker Culture in St. Petersburg, 1900-1929. Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2000 p.50

42. Emphasis mine

43. Herlihy, Patricia. “Joy of the Rus': Rites and Rituals of Russian Drinking” p.145

44. Phillips, Laura L. Bolsheviks and the Bottle Drink and Worker Culture in St. Petersburg, 1900-1929.p.52

45. ibid p.51

46. ibid p.56

47. ibid p.57

48. Phillips, Laura L. Bolsheviks and the Bottle Drink and Worker Culture in St. Petersburg, 1900-1929.p.58

49. ibid p.59

50. Hutchinson, J. F. “SCIENCE, POLITICS, AND THE ALCOHOL PROBLEM IN POST-1905 RUSSIA.” Slavonic and East European Review [Great Britain] 1980 58(2): p.234

51. ibid

52. ibid p.235

53. ibid

54. ibid p.253

55. Christian, David. “PROHIBITION IN RUSSIA 1914-1925.” p.89

56. Christian, David. ‘Living Water' Vodka and Russian Society on the Eve of Emancipation Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990 p.390

57. ibid. p.388

58. Christian, David. ‘Living Water' Vodka and Russian Society on the Eve of Emancipation p.388-389

59. White, Stephen. Russia goes dry: alcohol, state and society. Cambridge [England] : Cambridge University Press, 1996. p.20-21

60. ibid p.11

61. Christian, David. “PROHIBITION IN RUSSIA 1914-1925.” p.90

62. Christian, David. “PROHIBITION IN RUSSIA 1914-1925.” p.90

63. ibid p.104

64. ibid

65. ibid p.105

66. ibid

67. Christian, David. “PROHIBITION IN RUSSIA 1914-1925.” p.104

68. ibid p.107

69. Segal, Boris M. The Drunken Society Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in the Soviet Union A Comparative Study. p.50

70. ibid p. 47

71. Reed, John. Ten Days That Shook the World. England: Clays Ltd. Penguin Books, 1977 p.189

72. ibid

73. Marx, Karl and Frederick Engels. Manifesto of the Communist Party. 1848. Book on-line. Accessed 29 March, 2006. Available from http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/manifest.pdf . p. 19

74. Christian, David. “PROHIBITION IN RUSSIA 1914-1925.” p.118

75. ibid p.97

76. refer to pages 17-19

77. White, Stephen. Russia goes dry: alcohol, state and society. p.10

78. Snow, George E. “ALCOHOLISM IN THE RUSSIAN MILITARY: THE PUBLIC SPHERE AND THE TEMPERANCE DISCOURSE, 1883-1917” p.420

79. Segal, Boris M. The Drunken Society Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in the Soviet Union A Comparative Study. p.2

References

Christian, David. ‘Living Water' Vodka and Russian Society on the Eve of Emancipation Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990

Christian, David. “PROHIBITION IN RUSSIA 1914-1925.” Australian Slavonic and East European Studies [Australia] 1995 9(2): 89-118.

Herlihy, Patricia. “Joy of the Rus': Rites and Rituals of Russian Drinking”. In Russian Review. Vol. 50, No. 2 (Apr. 1991) pgs. 131-147.

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=00360341%28199104%2950%3A2%3C131%3AJOTRRA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-O

Herlihy, Patricia. The alcoholic empire: vodka & politics in late Imperial Russia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Hutchinson, J. F. “SCIENCE, POLITICS, AND THE ALCOHOL PROBLEM IN POST-1905 RUSSIA.” Slavonic and East European Review [Great Britain] 1980 58(2): 232-254.

Marx, Karl and Frederick Engels. Manifesto of the Communist Party. 1848. Book on-line. Accessed 29 March, 2006. Available from http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/manifest.pdf

Phillips, Laura L. Bolsheviks and the Bottle Drink and Worker Culture in St. Petersburg, 1900-1929. Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2000

Reed, John. Ten Days That Shook the World. England: Clays Ltd. Penguin Books, 1977

Segal, Boris M. The Drunken Society Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in the Soviet Union A Comparative Study. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1990.

Smith, R.E.F., et. al. Bread and Salt A social and economic history of food and drink in Russia. 1st ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Snow, George E. “ALCOHOLISM IN THE RUSSIAN MILITARY: THE PUBLIC SPHERE AND THE TEMPERANCE DISCOURSE, 1883-1917.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas [Germany] 1997 45(3): 417-431.

“Weight Conversion” Speck Design web space. Visited March 19, 2004 http://www.speckdesign.com/Tweight.html.

White, Stephen. Russia goes dry: alcohol, state and society. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1996.