Financial Success for the New Private Practice Chiropractor

Herman, David Matthew

Berea College Berea, Kentucky, USA

Abstract

Although clinical research is prevalent in chiropractic medicine, very little research exists on the business related aspects of chiropractic medicine and practice. Consequently, because business courses are limited in chiropractic education, a new chiropractor must establish and operate a private practice with limited business knowledge, often resulting in poor financial decisions. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to provide the new private practice chiropractor with optimal decisions that he or she can make enabling and guiding their financial success. Forty private practice chiropractors were contacted by telephone in Kentucky and Ohio with populations of 17,000 or less. A total research sample of ten chiropractors completed a structured survey of twenty-one questions using SelectSurveyASP Advanced software. Beginning in the 1970s, there has been a continuous rise in the debt acquired from chiropractic school, from an average of $25,000 to an average of $143,750 in the 2000s. The average amount of money that the sample needed to begin their private practice was $135,000. To cover their monthly expenses, the sample needed to earn an average of $4,200. The sample overwhelmingly agreed that the three most important attributes to a private practice chiropractor's success were receptionists/office managers, billing and collection specialists, and massage therapists. The sample also felt that for a new chiropractor to succeed, he or she must purchase a chiropractic table, diagnostic instruments, an x-ray system, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit, ultrasound unit, and a heat/cold therapy unit. The most successful advertisement mediums for recruiting new patients were patients' referrals and general word-of-mouth information. The overwhelming majority of the sample accepted some form of managed healthcare plan. On average, the sample was able to establish a self-sustaining private practice in three years. These findings will enable a new private practice chiropractor to make sound financial decisions.

Citation

Financial Success for the New Private Practice Chiropractor. Herman, David Matthew . Lethbridge Undergraduate Research Journal. Volume 4 Number 2. 2009.

Introduction

The use of chiropractic medicine in the United States has grown to a patient base of more than twenty million and is a multibillion dollar industry (Stevens, Mansfield, & Loudon, 2005). Chiropractic medicine is provided by approximately fifty thousand doctors across the United States, with many residing in rural and underserved populations (Stevens, Mansfield, & Loudon, 2005). Although clinical research is prevalent in chiropractic medicine, very little research exists on the business related aspects of chiropractic medicine and practice. Consequently, because business courses are limited in chiropractic education, a new chiropractor must establish and operate a private practice with limited business knowledge, often resulting in poor financial decisions. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to provide the new private practice chiropractor with optimal decisions that he or she can make that will enable and guide their financial success.

Review of Literature

According to the United States Small Business Administration (n.d.), in order to start a small business, one must complete a number of necessary steps to do so. Among these steps, one must select a location, choose a business structure, acquire the necessary licenses and permits, and decide on financing options that will meet short-term needs and long-term goals (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.).

Determining the correct location to begin a business can be a large factor in the business' success or failure (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). This can be illustrated by a good location saving a struggling business while a poor location could mean that even a well-run business may be in danger (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). According to Solovic (2004), before the entrepreneur begins a business in a specific location, he or she must research and fully understand the market at hand; this includes determining the amount of potential customers, establishing who the potential customers will be, knowing who your competition will be, determining how much your product will cost, and lastly, knowing what your advertising strategy will be.

In addition, one's location is also important when factoring in legal restrictions that are specific to the business (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). Since choosing a business structure will have long-term implications, it is recommended to consult with an accountant and attorney so that the correct business structure can be properly made for the owner (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). For a small business owner, one may choose from a sole proprietorship, limited liability company (LLC), general partnership, C Corporation, or S Corporation (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). Moreover, an accountant should be consulted because they will be able to give the entrepreneur valuable advice on the correct procedures of keeping the company's books (Klein, 2004). Additionally, the accountant will be capable of instructing the entrepreneur when to spend money and how to utilize tax-minimizing strategies (Klein, 2004).

Once the business structure has been chosen, one must consider state specific requirements such as a state business license, occupation and professional license, tax registration requirements, a trade number registration, and employer registrations (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). Due to state business licenses being the primary document required for tax purposes, small business assistance agencies within the state have been developed to aid small business owners in complying with state regulations (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). As a result of state licensure differences between states, physicians, for example, should contact their licensing authorities to ensure they have met necessary standards to practice (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). If the state in which the business resides has an income tax, the entrepreneur must contact the State Department of Revenue or Treasury Department to obtain an employer identification number (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). If in fact the business is to be run only in the local community, simply registering the company name with the state may suffice (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). Lastly, if an owner has hired employees, he or she will need to contact the State Department of Revenue or Department of Labor because he or she will most likely be required to make unemployment insurance contributions (United States Small Business Administration, n.d.).

Lastly, one must make financial projections as well as determining financial options that will meet short-term goals and long-term goals that should be detailed in a business plan (Klein, 2004; United States Small Business Administration, n.d.). Klein (2004) states that is vital for the entrepreneur to determine their business' start-up costs, and in doing so, not underestimating these costs. Klein (2004) goes on to say that in general, it takes the entrepreneur twice as long as they originally expected to reach desired sales levels. Likewise, in a study conducted by Jacobe (2006), 602 small business owners were interviewed; it was found that one in five reported their first-year profits as being less than they expected (Jacobe, 2006). Overall, Jacobe (2006) found that on average, small business owners reported that it took more than three years for their business to become profitable. In light of this, entrepreneurs need to ensure that they are adequately funded when beginning their business to decrease the possibility of finding themselves underfinanced down the road, which will increase their risk of failure if their business is not immediately successful and profitable (Klein, 2004; Jacobe, 2006).

Although the above demonstrates the necessary steps to begin a general small business, those steps can be transferred to any small business, such as a private chiropractic practice. Once the above steps have been completed, according to Counselman (1997), the most important aspect concerning a chiropractor's eventual success is directly connected with how well the chiropractor markets him or herself. Counselman (1997) states that the newly established chiropractor must not be too sparing with their money when it comes to marketing; Counselman (1997) instead asserts that the chiropractor must consider any advertising an investment in the future. However, Stevens, Mansfield, and Loudon (2005) found that only six percent of patients selected a chiropractor based on formal advertisements. Stevens et al. (2005) instead found that patients selected a chiropractor sixty percent of the time from a friend's referral; twenty-six percent reported word-of-mouth as the source; three percent were referred from a family doctor; and six percent of the respondents indicated their reason as other.

Unfortunately, very little information exists on the business related aspects of chiropractic medicine and practice. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine optimal decisions that new private practice chiropractors have made that enabled and guided their financial success. The research provided answers to questions regarding financial aspects of chiropractic medicine, such as start-up costs, and therefore determined trends that would better enable a new private practice chiropractor to make informed decisions as to the purchases that he or she makes.

Methodology

Participants

Forty private practice chiropractors were randomly selected from address and telephone numbers found on the Internet from Ohio and Kentucky with populations of 17,000 or less. Once selected, a telephone call was made to the chiropractor's office to determine if they were interested in participating in this study. A structured survey was created using SelectSurveyASP Advanced software and was available to the chiropractor on the Internet and anonymous to the researcher. Therefore, if in fact the chiropractor was willing, the link to the survey was given to them over the telephone, by email, or by fax machine. If the chiropractor did not have access to the Internet, the survey was sent to them as a fax and returned as a fax to the primary investigator of this study.

Experimental Design

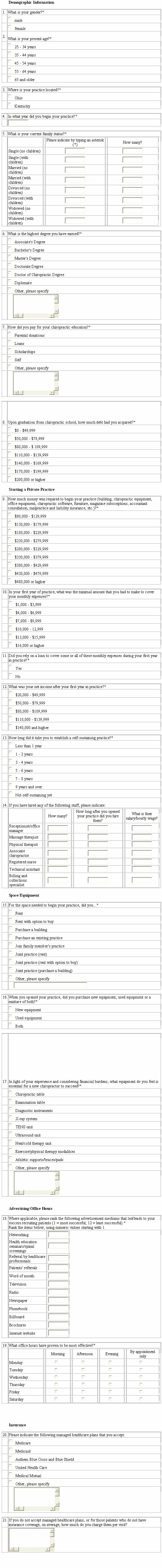

The survey consisted of five primary sections and twenty-one questions in total. The first section contained eight questions and demographic information about the participants, such as the age, gender, and current family status of the participant as well as the location of their practice.

The second section contained six questions as a new chiropractor and beginning a private practice, which included questions such as start-up costs, monthly expenses during the first year of practice, and the amount of time it took to establish a self-sustaining practice.

The third section contained three questions about the space and equipment needed to begin a private practice, such as the type of space chosen to begin a private practice and the type of equipment that is essential for a new chiropractor to succeed.

The fourth section contained two questions about advertisement mediums and office hours, such as the advertisement mediums chiropractors felt were most beneficial and the office hours that had proven to be most effective

The final section of the survey contained two questions and health insurance, such as managed health care plans that chiropractors accept and the fee charged to patients without health insurance.

Statistical Analyses

The majority of the questions on the survey were structured as multiple choice and resulted in dichotomous and ranged answers. The remaining questions were structured as fill-in-the-blank, categorical scale, check boxes, and one short answer. As a result, the data was interpreted by calculating the mean, range, and percentages that illustrated trends where applicable to draw conclusions.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of the Chiropractors

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic characteristics of the chiropractors that comprised this study. As illustrated, a total of ten completed surveys were obtained from the sample of forty, representing a response rate of twenty-five percent. Seventy percent of the sample was male and thirty percent was female, while twenty percent of the sample was between the ages of twenty-four to thirty-four years, forty-five to fifty-four years, and fifty-five to sixty-five years. Additionally, thirty percent of the sample was between the ages of thirty-five to forty-four years while ten percent of the sample was sixty-five years and over. With regard to family status, sixty percent of the sample was married with children, thirty percent was married with no children, and ten percent was single with no children. All ten (100%) of the chiropractors comprising the sample indicated that their highest degree earned was a degree of Doctor of Chiropractic. Six (60%) of the chiropractors owned a private practice in Kentucky while four (40%) of the chiropractors owned a private practice in Ohio. Furthermore, two (20%) of the chiropractors established their practice in the 1970s, three (30%) in the 1980s, and five (50%) in the 2000s. Five (50%) of the chiropractors funded their chiropractic education by loans, two (20%) by loans and their own funding, two (20%) by parental donations and their own funding, and one (10%) through full funding of their own. Upon graduating from chiropractic school, including living expenses, the chiropractors that graduated in the 1970s acquired an average debt of $25,000 with a range of $49,999; the chiropractors that graduated in the 1980s acquired an average debt of $75,000 with a range of $59,999; and the chiropractors that graduated in the 2000s acquired an average debt of $143,750 with a range of $120,000.

Starting a Chiropractic Private Practice

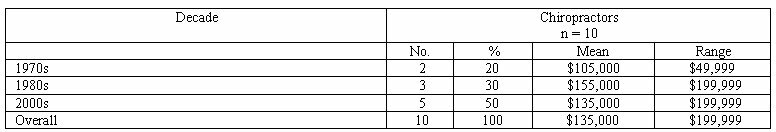

Table 2: Money Required to Begin Private Practice (By Decade)

Table 2 demonstrates, by decade, the amount of money that was needed for the ten (100%) chiropractors to begin their private practice. As illustrated, in the 1970s, two (20%) chiropractors needed an average of $105,000 to begin their private practice, with a range of $49,999. In the 1980s, three (30%) chiropractors needed an average of $155,000 to begin their private practice, with a range of $199,999. In the 2000s, five (50%) chiropractors needed an average of $135,000 to begin their private practice, with a range of $199,999. Collectively, the ten (100%) chiropractors had to earn an average of $135,000 to begin their private practice, with a range of $199,999.

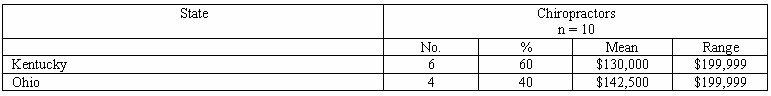

Table 3: Money Required to Begin Private Practice (By State)

Table 3 demonstrates, by state, the amount of money that was needed for the ten (100%) chiropractors to begin their private practice. As illustrated, six (60%) chiropractors in Kentucky needed an average of $130,000 to begin their private practice, with a range of $199,999. Conversely, four (40%) chiropractors in Ohio needed an average of $142,500 to begin their private practice, with a range also of $199,999.

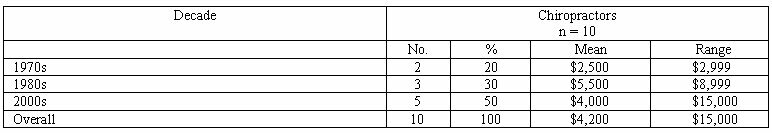

Table 4: Minimal Dollar Amount to Cover Monthly Expenses during First Year of Practice (By Decade)

Table 4 demonstrates the minimal amount of money that the ten (100%) chiropractors had to earn during their first year of practice to cover their monthly expenses, by decade. As illustrated, in the 1970s, two (20%) chiropractors needed to earn an average of $2,500 in order to cover their monthly expenses, with a range of $2,999. In the 1980s, three (30%) chiropractors were required to earn an average of $5,500 to cover their monthly expenses, with a range of $8,999. In the 2000s, five (50%) chiropractors needed to produce an average of $4,000 in order to cover their monthly expenses, with a range of $15,000. Overall, however, ten (100%) chiropractors needed to earn an average of $4,200 to cover their monthly expenses, with a range of $15,000.

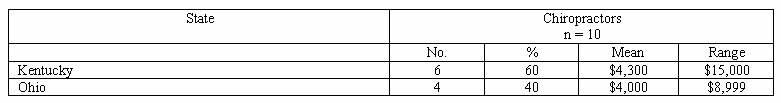

Table 5: Minimal Dollar Amount to Cover Monthly Expenses during First Year of Practice (By State)

Table 5 demonstrates the minimal amount of money that the ten (100%) chiropractors had to earn during their first year of practice to cover their monthly expenses, by state. As illustrated, six (60%) chiropractors needed to earn an average of $4,300 to cover their monthly expenses, with a range of $15,000; similarly, four (40%) chiropractors in Ohio needed to earn an average of $4,000 to cover their monthly expenses, with a range of $8,999.

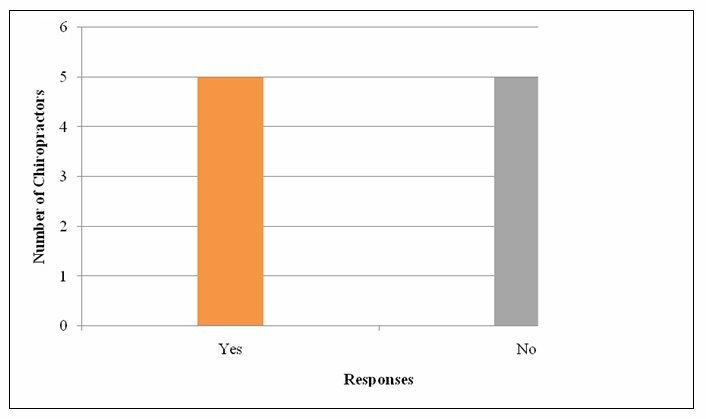

Figure 1: Reliance on a loan to cover monthly expenses during first year of practice.

Figure 1 demonstrates the responses of chiropractors and whether or not they relied on a loan to cover some or all of their monthly expenses during their first year of practice. As illustrated, five (50%) of the chiropractors did in fact rely on a loan to cover their monthly expenses. Figure 1 also illustrates that the remaining five (50%) chiropractors did not rely on a loan to cover their monthly expenses during their first year of practice.

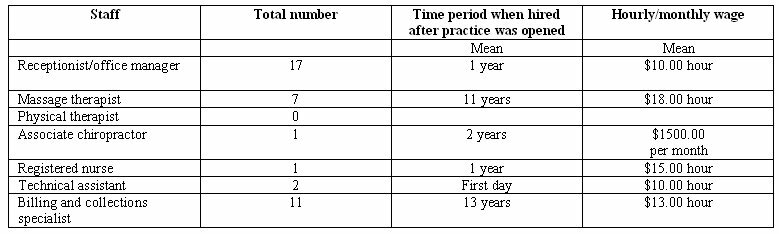

Table 6: Staff Hired by Chiropractors

Table 6 represents the employees that the chiropractors hired; including the total number of staff hired, the amount of time passed between the chiropractors opening their practice and hiring their employees, and the hour/monthly wage that the chiropractors paid their employees. As demonstrated, ten (100%) chiropractors hired seventeen receptionists/office managers after an average of one year in practice and were paid an average of $10.00 per hour; seven massage therapists were hired after an average of eleven years in practice and were paid an average of $18.00 per hour; one associate chiropractor was hired after two years in practice and was paid $1,500 per month; one registered nurse was hired after one year in practice and was paid $15.00 per hour; two technical assistants were hired on the first day of opening a practice and were paid an average of $10.00 per hour; lastly, eleven billing and collections specialists were hired after an average of thirteen years in practice and were paid an average of $13.00 per hour.

Space/Office Equipment for a Chiropractic Private Practice

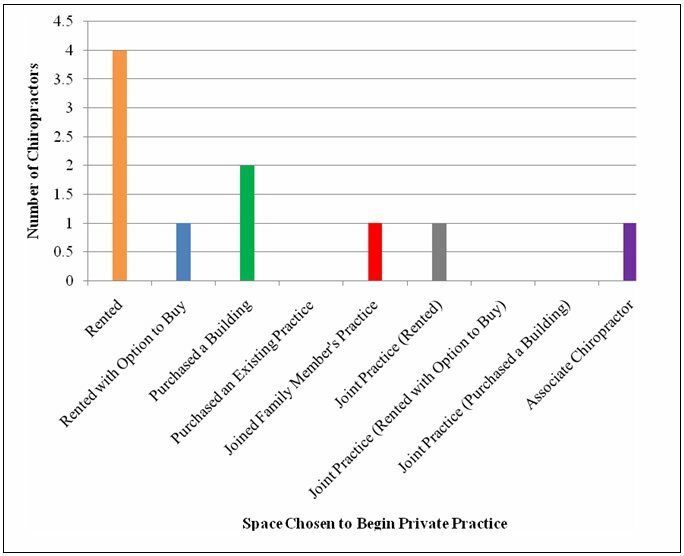

Figure 2: Space chosen to begin private practice.

Figure 2 demonstrates the space chosen by ten (100%) chiropractors when they began their private practice. As illustrated, four (40%) chiropractors rented a building; one (10%) chiropractor rented with the option to buy the building; two (20%) chiropractors purchased a building; none of the chiropractors purchased an existing practice; one (10%) chiropractor joined their family member's practice; one (10%) chiropractor established a joint practice that they rented; none of the chiropractors established a joint practice with the option to buy the building or a joint practice by purchasing the building; lastly, one (10%) chiropractor began by becoming an associate chiropractor to an already established chiropractor.

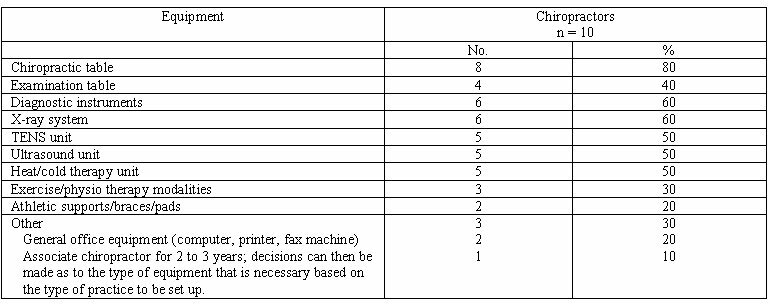

Table 7: Essential Equipment for a New Chiropractor's Success

Table 7 demonstrates the equipment that the chiropractors felt was necessary for a new chiropractor to succeed. As illustrated, eight (80%) of the chiropractors indicated a chiropractic table as being a necessity for a new chiropractor's success; four (40%) selected an examination table; six (60%) indicated diagnostic instruments and an x-ray system; five (50%) selected a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit, ultrasound unit, and heat/cold therapy unit; three (30%) selected exercise/physio therapy modalities; two (20%) indicated athletic supports/braces/pads; lastly, three (30%) selected “other”. Of those who selected “other”, two (20%) indicated general office equipment (computer, printer, fax machine) and one (10%) indicated that a new chiropractor should acquire a position as an associate chiropractor for two to three years and the decision can then be made as to the type of equipment that is necessary based on the type of practice to be set up.

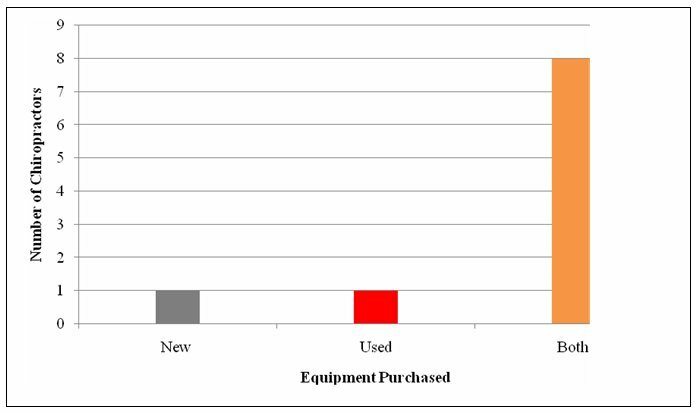

Figure 3: Equipment purchased for establishment of private practice.

Figure 3 demonstrates the equipment that the ten (100%) chiropractors purchased when they opened their private practice. As illustrated, one (10%) chiropractor purchased new equipment; one (10%) chiropractor purchased used equipment; and eight (80%) chiropractors purchased a mixture of new and used equipment.

Advertisement Mediums/Office Hours for a Chiropractic Private Practice

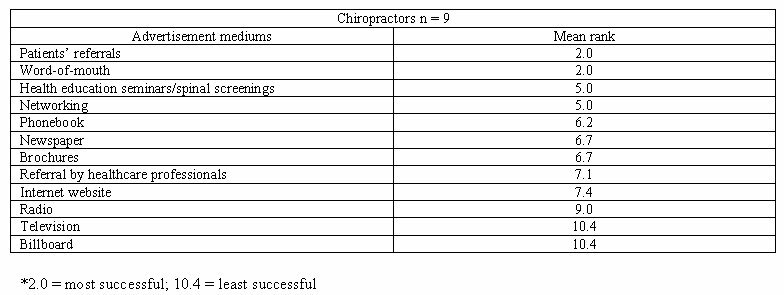

Table 8: Advertisement Mediums

Table 8 demonstrates the advertisement mediums that led to nine (100%) chiropractors' success in recruiting new patients. The chiropractors ranked the advertisement mediums on a Likert scale of one to twelve, with one being the most successful and twelve being the least successful. Once the researcher obtained the assigned values for each advertisement medium, a mean rank was then calculated for each advertisement medium. As illustrated, ten (100%) chiropractors felt that patients' referrals (2.0) and word of mouth (2.0) were most successful at recruiting new patients. The next two most successful advertisement mediums for ten (100%) chiropractors were health education seminars/spinal screenings (5.0) and networking (5.0), while the phonebook (6.2) was ranked as the fifth most successful advertisement medium. The newspaper (6.7) and brochures (6.7) were both ranked as sixth most successful, while referral by healthcare professionals (7.1) and internet (7.4) were ranked as eighth and ninth most successful, respectively. The radio (9.0) was ranked as tenth most successful, while the television (10.4) and billboard (10.4) were ranked as the eleventh and twelfth most successful advertisement mediums.

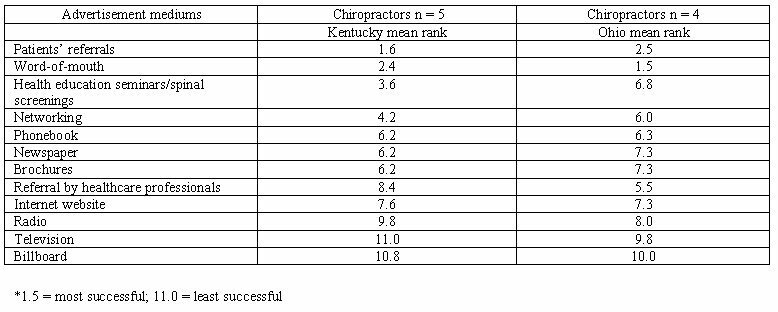

Table 9: Advertisement Mediums (By State)

Table 9 demonstrates by state the advertisement mediums that led to nine (100%) chiropractors' success in recruiting new patients. Once again, the researcher obtained the assigned values for each advertisement medium, and a mean rank was then calculated for each advertisement medium. As illustrated, the chiropractors in Kentucky felt that patients' referrals (1.6) followed by word of mouth (2.4) were most successful at gaining new patients, while the chiropractors in Ohio felt just the opposite; they felt that word of mouth (1.5) followed by patients' referrals (2.5) were most successful at gaining new patients. Next, the chiropractors in Kentucky indicated that health education seminars/spinal screenings (3.6) and networking (4.2) were the third and fourth most successful advertisement mediums, while the chiropractors in Ohio felt that referrals from healthcare professionals (5.5) and networking (6.0) were the third and fourth most successful mediums at recruiting new patients. For the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth most successful advertisement mediums, the chiropractors in Kentucky felt that the phonebook (6.2), newspaper (6.2), and brochures (6.2) were all equally successful, followed by the internet (7.6). Similarly, the chiropractors in Ohio felt that the phonebook (6.3) and health education seminars/spinal screenings (6.8) were the fifth and sixth most successful advertisement mediums, followed by the newspaper (7.3), brochures (7.3), and internet website (7.3) as being equally successful. As opposed to the chiropractors in Ohio, the chiropractors in Kentucky did not feel that referrals from healthcare professionals (8.4) were as successful, as they indicated this medium as being the ninth most successful form of recruiting new patients. However, the chiropractors in Kentucky and Ohio all agreed that the radio, television, and billboard advertisement mediums were the least successful forms of recruiting new patients, as the chiropractors in Kentucky ranked the radio as (9.8), television as (11.0), and billboard as (10.8), followed by the chiropractors in Ohio ranking the radio as (8.0), television as (9.8), and billboard as (10.0).

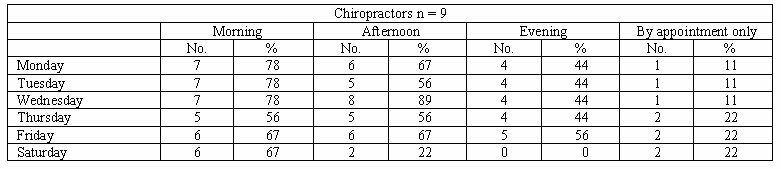

Table 10: Effective Office Hours

Table 10 demonstrates the office hours that proved to be most effective for the nine (100%) chiropractors. As illustrated, on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, seven (78%) chiropractors indicated morning hours to be most effective; while six (67%) selected afternoon hours on Monday, five (56%) indicated afternoon hours on Tuesday, and eight (89%) selected afternoon hours on Wednesday. On Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, four (44%) chiropractors felt that evening hours were most effective while one (11%) felt that appointments only were most effective. On Thursday, five (56%) indicated morning and afternoon hours to be most effective while four (44%) selected evening hours and two (22%) selected appointments only to be most effective. On Friday and Saturday, six (67%) felt that morning hours were most effective while six (67%) indicated afternoon hours on Friday and two (22%) indicated afternoon hours on Saturday. On Friday, five (56%) felt that evening hours were most effective, while none of the chiropractors felt that evening hours were effective on Saturday; however, on Friday and Saturday, two (22%) chiropractors indicated that appointments only were most effective.

Managed Health Care Plans Accepted/Fees of Chiropractic Private Practices

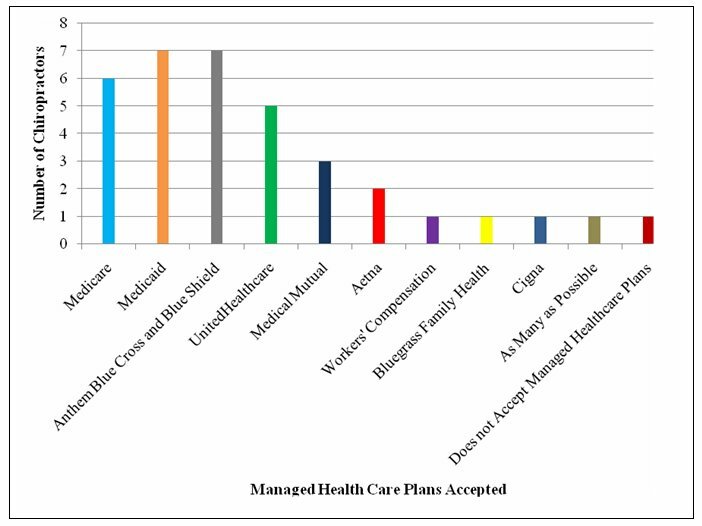

Figure 4: Managed healthcare plans accepted.

Figure 4 demonstrates the managed healthcare plans that eight chiropractors accepted at their private practices. As illustrated, six (75%) of the chiropractors accepted Medicare while seven (88%) accepted Medicaid and Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield. Five (63%) of the chiropractors accepted United Health Care and three (38%) accepted Medical Mutual, while two (25%) accepted Aetna. Figure 4 also demonstrates that one (13%) chiropractor accepted Workers' Compensation, Bluegrass Family Health, Cigna, as many managed health care plans as possible, and one (13%) chiropractor did not accept managed health care plans at their private practice.

Table 11: Managed Healthcare Plans (By State)

Table 11 demonstrates by state the managed health care plans that eight chiropractors accepted at their private practices. As illustrated, all five (100%) of the chiropractors in Kentucky accepted Medicare, Medicaid, and Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, while only one (33%) chiropractor in Ohio accepted Medicare and two (67%) accepted Medicaid, Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, United Health Care, and Medical Mutual. Next, three (60%) of the chiropractors in Kentucky accepted United Health Care while only one (20%) accepted Medical Mutual. As for Aetna, one (20%) chiropractor in Kentucky and one (33%) chiropractor in Ohio accepted this managed health care plan. One (33%) chiropractor in Ohio accepted Workers' Compensation while none (0%) of the chiropractors in Kentucky accepted this managed health care plan. One (20%) chiropractor in Kentucky accepted Bluegrass Family Health, Cigna, and as many managed health care plans as possible; whereas, none of the chiropractors in Ohio accepted these managed health care plans or the strategy of accepting as many as possible. Lastly, one (33%) chiropractor in Ohio indicated that he or she did not accept managed health care plans; whereas, all of the chiropractors in Kentucky accepted at least one managed health care plan.

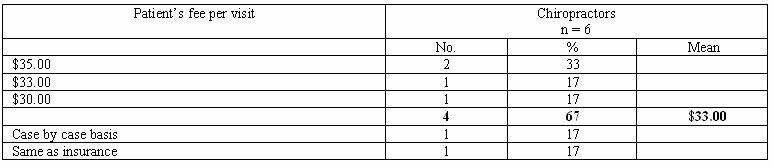

Table 12 : Patient's Fee per Visit (No Managed Healthcare Plan)

Table 12 demonstrates the fee that chiropractors charged their patients per visit for those that did not accept managed health care plans or for those patients who were not covered by a managed health care plan. As illustrated, two (33%) chiropractors charged their patients $35.00 per visit while one (17%) chiropractor charged his or her patients $33.00 per visit and $30.00 per visit; therefore, four (67%) chiropractors charged their patients an average of $33.00 per visit. Additionally, one (17%) chiropractor indicated that the fee they charged per visit was on a case by case basis and one (17%) chiropractor indicated that they charged the patient the same fee as a patient that was covered by a managed health care plan.

Establishment of a Self-Sustaining Chiropractic Private Practice

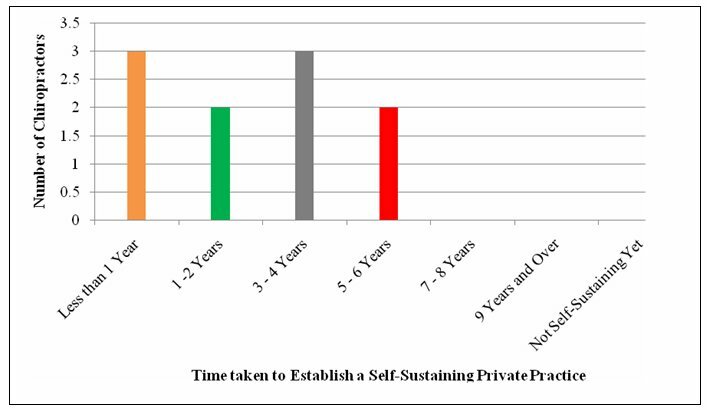

Figure 5: Time taken to establish a self-sustaining private practice.

Figure 5 demonstrates the amount of time that ten (100%) chiropractors needed to establish a self-sustaining private practice. As illustrated, three (30%) chiropractors established a self-sustaining private practice in less than one year and three to four years, while two (20%) chiropractors established a self-sustaining private practice in one to two years and five to six years. None of the chiropractors indicated that seven to eight years or nine years and over was needed to establish a self-sustaining private practice. Additionally, none of the chiropractors indicated that they had not established a self-sustaining practice.

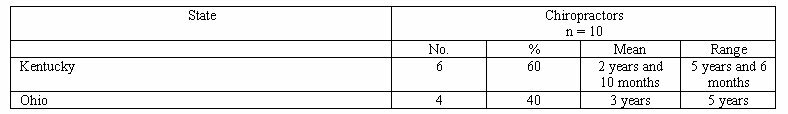

Table 13: Time taken to Establish a Self-Sustaining Private Practice (By State)

Table 13 demonstrates the amount of time that the ten (100%) chiropractors took to establish a self-sustaining private practice, by state. As illustrated, six (60%) chiropractors in Kentucky took an average of two years and ten months to establish a self-sustaining private practice, with a range of five years and six months. Similarly, four (40%) chiropractors in Ohio took an average of three years to establish a self-sustaining private practice, with a range of five years.

Discussion

As illustrated, the sample of chiropractors in this study were primarily male, average age forty-five years, married with children, from Kentucky (60%), opened their private practice in the 2000s (50%), and earned a degree of Doctor of Chiropractic as their highest degree. Since the average age of the sample was forty-five, it can be reasonably suggested that most chiropractors do not obtain a degree higher than that of Doctor of Chiropractic, such as a diplomate that would offer the chiropractor specialized knowledge. To the new chiropractor, this suggests that if he or she is interested in specialized care, this may be an auspicious route to pursue as the competition among chiropractors providing specialized care is low. However, this finding may also suggest that there is no demand for specialized care in chiropractic medicine, which would prove to be an unpromising route for the specialized chiropractor. With respect to the total debt acquired from chiropractic school, it was found that in the 1970s, the average debt for the sample was $25,000; whereas, in the 1980s, the average debt was $75,000; and in the 2000s, the average debt was $143,750, suggesting that the cost of education and living expenses for the aspiring chiropractor will continue to increase. Due to the increasingly high cost of education and living expenses, it is no wonder that the majority (50%) of the chiropractors paid for all of their education and living expenses by loans.

This study then explored the expenses that were related to starting a chiropractic private practice. In the 1970s, chiropractors needed an average of $105,000 to begin their private practice; whereas, in the 1980s, chiropractors needed an average of $155,000; and in the 2000s, chiropractors needed an average of $135,000. As evident, these values do not resemble the trend that appeared for the cost of education and living expenses while in chiropractic school. The first possible explanation for this is that the chiropractors who opened their private practice in the 2000s were more business savvy than were those that opened their private practice in the 1980s. Because chiropractic schools are now requiring students to complete business courses and the additional business seminars offered on weekends, the recently graduated chiropractor should have had an understanding of how to properly establish their private practice, which may in turn have yielded a lower start-up cost. The second possible explanation is that when opening a chiropractic private practice, the new chiropractor's start-up costs will largely resemble their individual philosophy, which resembles the type of equipment purchased, the employees hired, and the amount of space needed to begin their private practice. Thus, perhaps the chiropractors that opened their private practices in the 2000s were able to have a lower start-up cost than the chiropractors in the 1980s because they began with less equipment, less employees, and/or a smaller building. The third possible explanation is that it may have been more difficult for the chiropractors beginning their private practices in the 2000s to obtain a loan; thus, those chiropractors would be more limited financially than those that began their private practice in the 1980s. The last possible explanation may be due to the small sample size, which may have skewed the results. The money required to begin a private practice was then analyzed by state. In Kentucky, chiropractors needed an average of $130,000 to begin their private practice; whereas, in Ohio, chiropractors needed an average of $142,500, suggesting that it costs more to begin a private practice in Ohio. A possible explanation for this is that real estate may cost more in Ohio, thus increasing the start-up cost for chiropractors in Ohio. The amount of money that was needed for the chiropractors to earn and cover their monthly expenses during their first year of practice was then determined in order to give the new chiropractor an estimate of this value. By knowing this value, the new chiropractor can then make more educated decisions related to the financial decisions that he or she makes, increasing their likelihood of succeeding financially. In the 1970s, chiropractors needed to earn an average of $2,500 to cover their monthly expenses; whereas, in the 1980s, chiropractors needed to earn an average of $5,500; and in the 2000s, chiropractors needed to earn an average of $4,000. Again, possible reasons for lower monthly expenses in the 2000s than the 1980s may be due to more business savvy chiropractors who began their private practice in the 2000s, individual philosophies, an increased difficulty for chiropractors beginning their private practice in the 2000s to obtain a loan, and/or skewed results due to a small sample size. However, when analyzing this amount collectively, the chiropractors needed an average of $4,200 to cover their monthly expenses, providing the new chiropractor an accurate estimate that he or she can use in order to lay a successful foundation for their private practice. Additionally, this value was analyzed by state. In Kentucky, chiropractors needed to earn an average of $4,300 to cover their monthly expenses. Similarly, in Ohio, chiropractors needed to earn an average of $4,000 to cover their monthly expenses, suggesting that there is no difference between chiropractors in Kentucky and Ohio with respect to the amount needed to be earned and covering monthly expenses. Additionally, the percentage of chiropractors who relied on a loan to cover their monthly expenses was determined. While fifty percent of the chiropractors did in fact rely on a loan to cover their monthly expenses, fifty percent did not rely on a loan to cover their monthly expenses, suggesting that it is possible for the new chiropractor to earn enough money per month to prevent acquiring more debt from loans; however, it is just as likely for the new chiropractor to have to obtain a loan, which will increase their debt. The employees that the chiropractors hired was then determined, including the total number of staff hired and the amount of time that passed between the chiropractors opening their private practice and hiring their employees. The most hired employees were receptionists/office managers (17), billing and collection specialists (11), and massage therapists (7), suggesting that these occupations are the three most important attributes to a chiropractor's success in a private practice setting. However, on average, because the chiropractors did not hire these employees until one year, thirteen years, and eleven years, respectively, after they opened their private practice, it is evident that the new chiropractor is able to successfully run a private practice for an extended period of time before needing to hire employees. Perhaps the most obvious reason for this is that the new chiropractor must establish a patient base, and once the volume of patients becomes too large for the chiropractor to successfully manage the practice's many facets, the chiropractor must hire employees to reduce their workload and create a more efficient practice. As a result of these findings, it can be concluded that for the new chiropractor, hiring receptionists/office managers, billing and collection specialists, and massage therapists will yield the most success for their practice. Additionally, however, the findings also suggest that the new chiropractor can defer hiring these employees for an extended period of time, which will ultimately allow the new chiropractor to yield a greater net income.

When a new chiropractor establishes a private practice, there are many decisions and variables that must be considered; perhaps the most important is the type of space that he or she will acquire and the type of equipment that he or she will utilize. In order to provide the new chiropractor with a foundation for financial success and flexibility, this study examined these issues. With respect to the type of space that the chiropractors chose to begin their private practice, the majority (50%) chose to rent a building while the second most prevalent (20%) chose to purchase a building. This finding suggests that new chiropractors should in fact rent a building, allowing the new chiropractor more flexibility in the event that he or she wants to move the practice's location, which would be more difficult to accomplish if he or she purchased a building. When establishing a private practice, a new chiropractor must also decide what equipment he or she will utilize. For a new chiropractor to succeed, the sample most strongly (80%) felt that the new chiropractor should purchase a chiropractic table, followed by diagnostic instruments (60%) and an x-ray system (60%). Furthermore, fifty percent of the sample felt that a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit, ultrasound unit, and a heat/cold therapy unit were essential pieces of equipment for a new chiropractor's success. For the new chiropractor, by knowing these findings, he or she will curtail purchasing equipment that will only prove to be an unneeded financial burden. However, one should note that the process of purchasing equipment entails the type of practice to be set up, which is ultimately derived from the philosophy and/or the specialization of the new chiropractor. As a result, the new chiropractor should bear in mind their own philosophy and/or specialization when considering this finding. Once the new chiropractor determines the type of equipment that he or she feels is necessary, he or she must then decide whether to buy new equipment, used equipment, or a mixture of both. The overwhelming majority (80%) of the chiropractors purchased a mixture of new and used equipment, suggesting that if the equipment is in good condition, used equipment will suffice. Therefore, because used equipment is less expensive than new equipment, this is an avenue where new chiropractors can set themselves up for financial success by lowering their start-up costs.

Once the new chiropractor has established his or her private practice and purchased the necessary equipment, he or she must then recruit patients. In order to recruit patients, he or she must utilize effective advertisement mediums and office hours. The chiropractors felt that the most successful advertisement mediums at recruiting new patients were by patients' referrals (2.0) and by word-of-mouth (2.0), which is in agreement with the study conducted by Stevens, Mansfield, and Loudon (2005). This finding suggests that chiropractic patients are pleased with their care and are willing to voice their pleasure to potential patients. Also, in agreement with Stevens et al. (2005), this study found that referral by healthcare professionals is not a significant medium for chiropractors to gain new patients, suggesting that there is still a problem with the relationships between chiropractors and other healthcare professionals, such as medical doctors, (Stevens, Mansfield, & Loudon, 2005), or that other healthcare professionals are not knowledgeable about the benefits of chiropractic medicine. The effectiveness of the advertisement mediums were then analyzed by state. The most notable differences were that Kentucky gained more patients from health education seminars/spinal screenings (3.6) when compared to Ohio (6.8), and Ohio gained more patients from referrals from other healthcare professionals (5.5) when compared to Kentucky (8.4). This finding suggests that relationships between chiropractors and other healthcare professionals, such as medical doctors, may be better in Ohio than in Kentucky. With respect to office hours, the majority of the chiropractors felt that the most effective office hours were in the morning on Monday (78%), Tuesday (78%), and Saturday (78%); whereas, in the afternoon on Wednesday (89%); and in the morning and afternoon on Thursday (56%) and Friday (67%). Additionally, because of the low percentages of appointments only on Monday through Saturday, it can be concluded that all of the chiropractors accept a considerable amount of walk-ins. For the new chiropractor, these results can better enable them to most effectively reach potential patients and at the same time reduce costs, such as electricity bills, at times when hours have proven to be ineffective.

When opening a private practice, the new chiropractor must also take into account managed healthcare plans. The most accepted managed healthcare plans by the chiropractors were Medicaid (88%) and Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield (88%). The next four most accepted managed healthcare plans were Medicare (75%), UnitedHealthcare (63%), Medical Mutual (38%), and Aetna (25%). Furthermore, one (13%) chiropractor indicated that they accepted as many managed healthcare plans as possible, while only one (13%) chiropractor indicated that they did not accept any managed healthcare plans. This finding suggests to the new chiropractor that in order to have the ability to treat most of the population, he or she should accept managed healthcare plans. The managed healthcare plans were then analyzed by state. The most notable differences were that all of the chiropractors in Kentucky accepted Medicare, Medicaid, and Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, whereas only thirty-three percent of the chiropractors in Ohio accepted Medicare and sixty-seven percent accepted Medicaid and Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield. As a result, this finding suggests that perhaps chiropractors in Kentucky treat patients that are of older age than do chiropractors in Ohio. Additionally, for the chiropractors who did not accept managed healthcare plans or for those patients that were not covered by managed healthcare plans, the fee that the chiropractors charged the patient per visit was determined. On average, the chiropractors charged their patients $33.00 per visit. This finding is especially helpful for the new chiropractor when he or she is determining a fee that patients are willing to pay.

Lastly, the new chiropractor should have a timeline as to when he or she thinks they will have established a self-sustaining private practice. By knowing this, he or she will be better enabled to make financial decisions. In this study, it was found that thirty percent of the chiropractors were able to establish a self-sustaining private practice in less than one year and three to four years, while twenty percent of the chiropractors were able to establish a self-sustaining private practice in one to two years and five to six years. This result gives the new chiropractor a workable timeline that he or she can use to base their financial decisions on. Additionally, this data was analyzed by state. In Kentucky, the average amount of time that was needed for the chiropractors to establish a self-sustaining private practice was two years and ten months; similarly, in Ohio, the average amount of time was three years. This finding suggests that there is no difference in the amount of time that it takes for a chiropractor in Kentucky or Ohio to establish a self-sustaining private practice.

Conclusion

Beginning in the 1970s, there has been a continuous rise in the debt acquired from chiropractic school, from an average of $25,000 to an average of $143,750 in the 2000s. The average amount of money that the sample needed to begin their private practice was $135,000. To cover their monthly expenses, the sample needed to earn an average of $4,200. The sample overwhelmingly agreed that the three most important attributes to a private practice chiropractor's success were receptionists/office managers, billing and collection specialists, and massage therapists. The sample also felt that for a new chiropractor to succeed, he or she must purchase a chiropractic table, diagnostic instruments, an x-ray system, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit, ultrasound unit, and a heat/cold therapy unit. The most successful advertisement mediums for recruiting new patients were patients' referrals and general word-of-mouth information. The sample felt that the most effective office hours were in the morning on Monday, Tuesday, and Saturday; whereas, in the afternoon on Wednesday; and in the morning and afternoon on Thursday and Friday. The overwhelming majority of the sample purchased a mixture of new and used equipment and accepted some form of managed healthcare plan. On average, the sample was able to establish a self-sustaining private practice in three years. These findings will enable a new private practice chiropractor to make sound financial decisions.

Limitations and Future Research

This study had a small sample size, and therefore, presents limitations. Consequently, trends and conclusions may present inaccurately. Most notably, when comparing the data between states, the sample size was reduced by approximately one-half, and therefore, may present problematic data. In future research, in order to develop more useful trends and conclusions, a larger sample size should be employed.

About the author

My name is David Matthew Herman, and I am a senior at Berea College in Berea, Kentucky. I am majoring in Physical Education with a concentration in Exercise Science and Sports Medicine. Upon graduation from Berea College, I will be attending Palmer College of Chiropractic in Davenport, Iowa, beginning in July of 2009.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Martha Beagle, Full Professor of Physical Education, for her guidance and assistance during my research project.

Appendix: Survey

References

Counselman, T. E. (1997). Success! for the new chiropractor. Topeka: LivLife.

Jacobe, D. (2006, September 18). Lessons learned about starting a small business: Small business owners share what would have made starting their business easier. Gallup Poll Briefing, 5-8.

Klein, K. E. (2004, December 27). Simple startup flubs to avoid. Business Week Online, pN.PAG, 0p.

Solovic, S. W. (2004). Ten common mistakes start-up businesses make. Women in Business, 56 (3), 26-27.

Stevens, R., Mansfield, P., and Loudon, D. (2005). The public's image of chiropractic services: A pilot study. Services Marketing Quarterly, 26 (4), 19-37.

United States Small Business Administration. (n.d.). Small business planner: Start your business. Retrieved October 21, 2008, from http://www.sba.gov/smallbusinessplanner/start/index.html