Globalization and the Transcendence of Democracy

Shruhan, Matthew

The George Washington University Washington, D.C., USA

Citation

Globalization and the Transcendence of Democracy. Shruhan, Matthew . Lethbridge Undergraduate Research Journal. Volume 4 Number 2. 2009.

A Democratic Recession?

Samuel Huntington divides democratization over the past 200 years into three waves that reflect the transitions states have undergone from authoritarianism to democracy. Each wave of democracy, however, witnessed a recession in which a number of states reverted back to authoritarian forms of government.1 The third wave is of key importance today because it also encompasses another type of democratic recession involving the decline of territorially-based civil society and political participation, and it simultaneously serves as the basis from which a new form of democracy is beginning to emerge.

In terms of declining civil society and civic participation, contemporary democracy in the United States has been negatively affected by globalization. Although citizens have many of the civil liberties associated with liberal democracies, simply possessing a right is not equivalent to invoking it. Bill McKibben, for instance, believes we have shirked our responsibilities as members of our communities and have instead become citizens of ourselves, or hyper-individualists2. The role of the individual has become so salient that it poses the question: Has democracy gone so far that it no longer represents the will of the people but rather an aggregation of individuals? The pragmatist philosopher Judith Greene expands on this point and elucidates an institutional explanation for the negative effects of democracy in the United States:

…The great American divides of race, class, and gender that…progressives confidently believed were being eliminated as the idea of democracy gained momentum have instead angrily revived like monsters sighting new prey during a time of famine…The practical meaning of this backlash has been millions of homeless men, women, and children; an increase in domestic violence; and a growing gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ that seems to be creating a permanent urban underclass.3

Greene believes that American representative institutions, the cornerstone of democracy in the United States, have failed us. Technology has divided us and our communities, spreading inequality, hardly a value democracy advocates.

While traditional means of representation have certainly produced positive results in many democracies around the world, they are no longer and should no longer be the sole means of democratic representation in today’s globalized world. As a result of globalization, there has been a growing sense of interconnectedness among states, economies, cultures, and individuals. A prominent feature of contemporary globalization is the multiple loci of power in the global arena, with territorial states no longer being the sole actors. Other actors, such as individuals, technology, corporations, NGOs, and IGOs now shape inputs and outputs in the global system.

The effects of this interconnectedness can be seen not only in the global sphere of diplomacy, multinational corporations, and the internet, but also in the local sphere of urban centers and rural communities. Although many of the outputs of globalization have propelled the hyper-individualist tendencies that are prevalent in liberal democracies, globalization has also simultaneously produced a juxtaposing effect; democracies of communalism, tolerance, participation, and empowerment that have allowed local communities to accomplish that which traditional liberal democracy left unfinished. Now some citizens have witnessed an increase in their efficacy, or their capacity to affect change in a system. Individuals and non-state actors, such as NGOs, are now increasingly able to transcend state boundaries and potentially produce desired effects on a global scale through remodeling democracy at the local level, which is evident in the emergence of a new form of governance—transcendent democracy—developing in the midst of the recession of the third wave.

Transcendent democracies abound in an era of instability, which would initially seem to threaten their viability. Yet, transcendent democracies, due to their unique complex and adaptive features are effectively using the turbulent era to grow and proliferate in the age of contemporary globalization. Despite its plethora of definitions and forms, most scholars can agree on one outcome of contemporary globalization—it has made the world more complex. I believe that Rosenau’s theory of fragmegration 4 accurately conceptualizes the complex system that is human society.5 A complex system is composed of a non-linear arrangement inputs and outputs, and these components mutually reinforce each other through interaction. In essence, one event does not simply cause another, which then causes another. Many events simultaneously interact to affect the system as a whole, which begins to take on a function that is greater than the sum of its parts. The components of human society (including non-state actors at both the local and global levels) form this complex system of interactions and feedback. Governance systems fail when they do not recognize these tensions, which partially explain the democratic recession of the third wave. Increasingly polarized methods of top-down (authoritarianism in Iran) and bottom-up (anarchy in Somalia) ‘governance’ have contributed to increased clientelism, ethnic conflict, a decline in civil society, and environmental degradation.

In order to be effective a system of governance must reflect the complexities of the sphere in which it is created to govern. Fortunately, there seems to be an emerging localized trend, perhaps the beginnings of a fourth wave of democracy, that seek to reverse the apathy, inequality, and decline in social capital6 in order to create a deeper, more meaningful transcendent democracy. Harnessing this powerful force of change and utilizing the advantages of increased interconnectedness can help catalyze a wave of transcendent, pragmatic governance that recognizes the inherent complexities of the globalized world and can perhaps help resolve problems of inequality, poverty, and environmental degradation.

Returning To The Laboratory

The emergent fourth wave, as it may be seen in the future, is a break from its predecessors, hence the term transcendent democracy. While the first three waves have mostly emphasized the same model of representative democracy, transcendent democracy looks deeper into both citizens and the societies they construct. Its purpose is to revitalize the effectiveness of governance, beginning with the local and culminating in the global sphere. Contemporary globalization allows for the increased presence of catalysts to transcendent democracy in local communities, which work with citizens to build effective models of governance. Due to globalization, federalism, and state sovereignty these local democracies do not exist in isolation but are rather part of numerous local, state, regional, international, and global networks. In addition globalization has allowed actors from the global and local spheres across the world to transcend spatial boundaries and affect changes across a wide spatial spectrum. The precise blueprints for this model are as dynamic as the world they seek to govern and will evolve, but they nevertheless contain aspects of a mobius-web7 style of governance.

The mobius-web model seeks to mirror the complexities of a fragmegrative world. Its blueprint of governance is composed of “both hierarchical and networked interactions across levels of aggregation that may encompass all the diverse collectivities and individuals who participate in the processes of governance.”8 Many of the shortcomings of representative democracy in the United States and developing countries stem from its inherently top-down form of governance. The somewhat monopoly of top-down governance impedes the development of effective bottom-up methods, such as community associations. Rosenau asserts that opposition groups are not amenable to centralized authority, and it is therefore likely that they will resist, resulting in less than effective policy-making and implementation.9

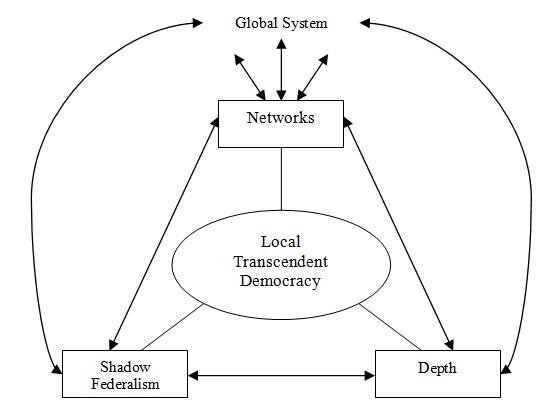

The emergent features of transcendent democracies utilize Rosenau’s mobius-web model as a framework and add to it three main components: depth, shadow federalism, and network governance. Depth involves the subcomponents of deliberative processes and process leaders. Shadow federalism is a de facto delegation of authority to actors that fill in a power vacuum, and network governance connects the internal components of transcendent democracies to each other and with the rest of the world, consistent with the complexities of fragmegration.

These components mutually reinforce each other. For example, evident in Mumbai, deliberative processes of depth and networks helped to promote shadow federalism. Slum communities, with the help of networked NGOs, launched housing programs and community exchange programs (to promote dialogue), which allowed slum communities to begin to take on some of the responsibilities that the state government had neglected.10 It is important to note that although these components mutually reinforce each other, the main reason they have the ability to do so is because forces of globalization allow supraterritorial actors to penetrate and shape transcendent democracies by using any of the three main components as entry points, evident from the cases of Mumbai and Porto Alegre.

Figure 1: A Local Transcendent Democracy

Depth

Globalization and the third wave (and perhaps recession) of democracy have caused an increase in violence, leading to fragmentation in many societies. In this instance fragmentation originates from what I call geographic respatialization—a rendering of distant as proximate—one of the aspects that Rosenau discusses in his theory of fragmegration. For example, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India worked to rewrite “the geography of India as Hindu geography…[and] combined [it] with a paranoid nationalist geography, in which Pakistan was treated as an abomination.”11 Ethnic tensions such as this are a major contributor to societal destabilization and it would seem that many of these conflicts, due to their historical origins, are irreconcilable. Some communities in India, however, are transcending these constraints to development and attain new characteristics of depth. Depth is the process of introspection; in terms of democracy and development, it refers to looking inward to one’s self and to one’s community as a basis for building a stable and effective society at the local level. David Held, in his description of the increasing intensity in globalization processes12 , tangentially touches upon this point when referring to the increasing hold that globalization has in society today. The concept of depth is a broader abstraction of Held’s theory, referring to the role that the individual, through introspection, has on the community and its collective consciousness. In other words, by viewing themselves as part of a community, be it local, global, or supraterritorial, individuals contribute to the increased intensity of mental connections between members of a given community. Network governance allows local collective consciousness to become global consciousness—an individual’s understanding of human interconnectivity inherent in the world-system—which can potentially provide global solutions to global issues.

Through increased dialogue among community members, new deeply democratic norms become engrained in the culture, which are critical for development. For example, listening to the opinions of others before advocating an opinion, reflecting on one’s values, and collectively imagining of possible futures13 allow citizens to band together to accomplish goals that benefit the local community. These democratic values deepen participatory practices by allowing a greater number of opinions to be heard. Deep democracies accomplish this through a number of different methods of civic engagement that bring members from diverse cross-sections of society together: (1) deliberation [citizens’ summits, national issues forums, consensus conferences, etc.]; (2) dialogue [dialogue circles, compassionate listening, etc.]; (3) collaborative action [policy dialogues, compassionate listening, etc.]; (4) community conflict resolution [healing circles, community conferences, community mediation, etc.].14 These components of deep democracy supplement traditional representative institutions and deepen the penetration of democracy into underrepresented portions of society. Citizens in these participatory bodies now have a stake in decision-making, in which they previously had little. They are directly responsible for the success or failure of their communities, and processes of depth seem to be originating in impoverished communities because they have the most to gain, in terms of socioeconomic benefits, from such a form of democracy.

Processes of deliberation are composed of “arguments by and to participants committed to rationality and impartiality.”15 Through deliberation, individuals must renegotiate their priorities and form a consensus with a diverse group of citizens. Liberal-virtue theories of deliberation “seek to bring together the notions of procedural norms and virtuous attitudes and…behavior[s]—and which, therefore, typically make more…reference to concrete deliberative models…and practices.”16 There is an essentially dual and fragmegrative nature in transcendent democratic deliberative processes. Liberal deliberative theories (improving institutions and procedural practices) and virtue deliberative theories (concentrating on the creation of “virtuous dispositions”17 ) are both present and necessary for developing effective intra-community dialogue. They mutually reinforce each other, such as in the Participatory Budget in Porto Alegre, Brazil, where changes in procedural norms yield changes in citizens’ attitudes toward civic engagement. These changes in civic engagement likewise yield more regulatory changes and citizens begin to allocate funding for community necessities.

Genuinely deliberative discussion yields justice, not self-interest18 where individuals act out of selfish motives which conflict with the needs of the community, so this method is perhaps an effective way to deal with the problem of special interests in deeply democratic communities. Many special interests stem from the state or organizations comparable in size, but since the premise of deliberation revolves around empowering the individual to deepen connections with their community to solve community-level problems (especially in areas neglected by the state), they are driven to create solutions that do not involve solely state help, partially avoiding the widespread clientelism that characterizes many of the states that house deeply democratic communities. Communities must therefore rely on the creativity of the individuals that comprise them in order to develop effective solutions. In addition, community forums, as a result of interaction with diverse groups of citizens, are a way to acquire new skills and knowledge that enable citizens to respond without state intervention.19 Aspects of deliberation are present in all four sub-sections of civic engagement listed above, and these aspects work to enhance economic and social well-being, as will be seen in many of the case studies discussed below.

The participation of many community members is of course crucial to the success of deeply democratic exercises, yet despite the overarching emphasis on the collective whole, the role of the individual as a catalyst in deeply democratic communities and in transcendent democracies at large is crucial. Micro actors are no longer constants in global affairs. Due to increasing skill sets and the processes of fragmegration, people have “become more engaged, more involved, more able to shape their world.”20 But transcendent democracies instead utilize the capabilities of individuals in the form of process leaders—”the one[s] who facilitates the experience of participatory consciousness.”21 Process leaders play a key role in implementing the deliberative processes that are so important in creating local solutions to both local and global problems. These individuals helped implement many of the deeply democratic initiatives discussed below. The hypothesis of depth in transcendent democracies needs a suitable testing ground to assess its validity.

Cities As The Experimental Unit

The concept of depth necessitates the presence of a diverse community working together to accomplish tasks that an individual cannot accomplish alone. Cities provide this diversity, but there exists debate as to whether or not cities are catalysts for depth or breeding grounds for the hyper-individualist consumer culture and discrimination.22 The debate revolves around the presence (or lack thereof) of public space, which is crucial to developing a sense of depth in a community, and thus, an essential steppingstone to becoming a fourth wave democracy. While urban areas have larger populations and are thus more likely to have more public spaces, such as public parks, we should not, according to Amin and Thrift, the emergence of civic virtue simply because of the presence of public spaces.23 Rather, repeated interaction in these public spaces, not merely the spaces themselves, fosters the ideals of a transcendent democracy at the local level. While many communities are politically apathetic, those communities in particular that are negatively affected by traditional representative democracy will potentially forego apathy and utilize the public spaces of the urban to engage in dialogue and formulate solutions.

Cities are also an appropriate experimental unit because they, as a result of larger populations and of generally having more governmental presence, are more likely to possess the resources necessary to combat problems for their populations. And due to massive migration, most prevalent in developing states, many developmental problems are present in urban areas (This is not to downplay the gravity of rural problems but only to assert that urban problems, especially in slums, are just as prevalent.). These urban problems are a direct result of the socio-spatial forces to which cities are subject. For example, many economically deprived neighborhoods, such as slums, are subject to what I call the downward spiral effect. Andersen alludes to this phenomenon and believes that deprived neighborhoods are not merely a result of social inequality, but that they perpetuate it as well. These areas create new segregations because they attract more poor citizens and tend to generate more social problems; this in turn works to repel other citizens and economic resources, which could potentially provide the skills and capital to revitalize the neighborhood.24 Cities therefore possess the human capital and economic resources to combat these issues but in many cases do not utilize them. Transcendent democratic trends, however, are at work attempting to reverse this.

At this point, the role of globalization in promoting transcendent democracies may seem to remain unclear. It would appear that globalization has left deprived urban areas (not to mention rural areas) relatively untouched in terms of economic interdependence and cultural influence, but this analysis is based on an overly simplistic conception of globalization as a largely nationally-based phenomenon. In contrast transcendent democracies rely on the supraterritorial25 features of contemporary globalization to form systems of dynamic network governance at both the global and local levels. Cities remain an appropriate experimental unit to test the features of depth that characterize transcendent democracies precisely because of their unique position on the frontier of both the local and the global, where they may have “become the sites where the unbundling of the state takes place.”26 Because of this “unbundling”, there emerges a space for supraterritorial actors to penetrate the urban setting, which places cities in a unique position to modify the structures of authority by acknowledging the importance of the global-local network of interactions. Viewing globalization as an inherently complex, integrative phenomenon involving both of these spheres requires that an experimental unit possess the same characteristics. As cities are rapidly growing around the world, the prospects for the growth and development of transcendent democracies are potentially increasing.

A Problem of Control?

Units in an experimental group need to be uniform and all conditions must be constant (save the variable being tested) in order to obtain reliable results. Because urban experimental units do not exist in isolation, these experimental units are not identical or constant, and it is sometimes difficult to determine to what extent certain actors are influencing transcendent democratic change in local communities. In other words, urban experimental units carry with them many of the same problems that sometimes plague signal to noise ratios in statistics. Noise refers to the variance within a group, while signal refers to the variance among groups. However, if the noise is too large, any comparison made between the groups will not be reliable because excessive variation in each individual group makes it harder to produce a reliable individual group results and thus harder to compare that mean with those of other groups.

Globalization has caused this problem to occur when attempting to observe phenomena in urban experimental units. Because globalization has made much of the world, especially cities, more interconnected and perhaps more interdependent, cities are not entirely independent experimental units. This suggests that large quantities of noise (i.e. interactions with other local and global units in the complex world system) impede a precise determination of the impacts of state and non-state actors on urban areas. Yet, this problem could actually be beneficial in terms of the proliferation of transcendent democracy. Information and ideas (such as components of deep democracy and deliberation) now have great potential to spread to other areas, such as the spread of participatory budget movements originating in Porto Alegre to other cities in Brazil. As more areas become transcendent democracies, the potential for feedback loops across the global system is high, increasing the prospects for a fragmegrative system of network governance based on principles of mobius-web governance. What follows is an examination and analysis of the practical implementations of elements of transcendent democracies in numerous world regions and how non-state actors are utilizing their newly prominent roles in cultivating and perpetuating these democratic changes.

Slum Upgrading in Mumbai

The inequality that is a characteristic of the third wave of democracy is certainly present in India—the world’s largest democracy. Approximately forty percent of the population of Mumbai, the focus of this case study, live in slums, and yet occupy only about eight percent of the city’s land.27 Furthermore, citizens who live in slums are often neglected by their governments and have “negligible access to essential services, such as running water, electricity and ration cards for food staples.”28 An alliance of NGOs and grassroots movements has emerged in Mumbai in an attempt to alleviate some of the problems that exist in slums through a process known as slum upgrading.

The Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC) is a globally-networked, India-based group of NGOs that works to support two grassroots movements—the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) and Mahila Milan (MM). These two movements have organized hundreds of thousands of slum and pavement dwellers, including women, to help address and solve slum-related issues, such as sanitation and affordable housing.29 Not only does this alliance attempt to unite slum communities, but it also interestingly involves people who might be prematurely classified as members of Rosenau’s circumstantial passives—those “whose daily concerns are such as to leave them no time, energy, or resources to care about anything beyond their daily efforts to maintain their subsistence.”30 NSDF and MM, however, are working to thin the ranks of the circumstantial passives in order increase the political efficacy of the poor to solve problems that their elected governments cannot or will not handle. This de facto delegation of power to NGOs, grassroots organizations, and communities is a component of transcendent democracy known as shadow federalism, in which non-state actors take charge due to a vacuum of power because there is little government intervention in slum areas. In addition to the overarching concept of shadow federalism that serves as the basis for slum community development in Mumbai, a number of other transcendent democratic methods are working to solve these local problems.

In terms of increasing depth, SPARC has established community resource centers, savings and credit programs, exchanges with other slum communities (which could also be viewed as networking), affordable housing and toilet exhibitions and pilot projects, and advocating for pro-poor policies within the established democratic regime.31 These processes exemplify the concept of depth because they encourage greater dialogue and deliberation within and between communities. Furthermore, individuals become more empowered and increase their sense of efficacy through community surveys, which encourage community members “to collect all details related to socio-economic conditions such as housing, sanitation, water, income and education at the individual, household and settlement level” so that they are in a more favorable position upon negotiation with government officials.32 During peer exchanges, community members travel to other slum communities to share experiences and advice, which serves to build a sense of community among these previously isolated areas.33 A sense of community is critical to deliberative processes that occur with state and non-state actors because the community will have common and unified goals that they feel need to be accomplished. To facilitate these deliberative processes, SPARC is part of a network and has aligned itself with many state and non-state actors, including: civil servants responsible for housing loans and slum rehabilitation; railways, the Port Authority, and the Bombay Electric Supply and Transport Corporation; municipal authorities who control critical elements of the water supply and sanitation infrastructure.34

While this network alliance has achieved many goals, such as pioneering resettlement initiatives, I believe one of the most important successes is its utilization of the supraterritorial networks of globalization to not only affect change within Mumbai, but also to expand the network and spread its initiatives to other areas of India and even around the world. For example, these resettlement efforts have spread to Kenya, expanding the possibility of the formation of transcendent democracies and the network of connections between them. According to Sheela Patel:

I went to Kibera, one of the largest informal settlements in Nairobi, and while I was there I saw that a railway line passed through that slum, and the shops and dwellings hugged the track and were constantly being demolished only to come up again. Although the issue of slums along the railway tracks was not the focus of my visit I was struck by the similarity of the situation with the case of Mumbai only 5 years ago.35

Patel describes how slum dwellers in different locations are confronting many of the same issues, which amplifies the importance of peer exchanges and dialogues to create a cohesive community network, in this case one across national borders. Patel advised the Kenyan counterpart of SPARC in Kenya to suggest that representatives from the Kenyan government and local community travel to Mumbai to learn about the SPARC resettlement initiative. Upon traveling to Mumbai and after “many discussions…with NSDF and Mahila Milan communities as well as the Indian Railway officials… they agreed to explore how they would also undertake a similar partnership in Nairobi.”36

The trip to Mumbai and interaction with other communities changed the perspectives of both Kenyan community members and government officials. Members of the community were able to view themselves as Kenyans once they were abroad, perhaps a preliminary step away from their sphere of the circumstantial passives. The government officials, likewise, “began to see their larger goals…[of] improving the lives of their fellow Kenyans”37 and treating slum dwellers as citizens, not merely components of the slum structure. The hybrid liberal-virtue theory of deliberation was essentially exported to Kenya as a result of the mutually reinforcing interaction of NGOs and community leaders through global and local connections, which allowed for components of transcendent democracy to take hold in new areas. This phenomenon has important implications for federalism and delegation of authority in national governments. In Mumbai and Nairobi shadow federalism has been slightly modified in the wake of transcendent democratic successes. Instead of non-state actors and local communities simply working to fill a void in governance, transcendent democratic practices of deliberation and community empowerment are forging new structures of shadow federalism, in which a network of governmental and non-governmental actors, led by process leaders, work to fill this void. Mumbai is thus an apt example of the three components of transcendent democracies simultaneously functioning to reinforce each other in a complex, transcendent democratic system.

The Participatory Budget of Porto Alegre, Brazil

Even in the midst of the third wave of democracy, transcendent democratic movements, using processes of depth, shadow federalism, and network governance, had already begun to emerge. The Brazilian Workers’ Party38 (PT) won municipal elections in the city of Porto Alegre in 1988. The successes of the city’s infamous instance of transcendent democratic initiatives—the Participatory Budget (PB)—have allowed the program to spread to over 100 Brazilian cities by 2000.39 An important difference in the experience of Mumbai and Porto Alegre is the type of networks utilized. Networks in Mumbai were composed of mainly NGOs, grassroots organizations, government departments, and local communities; due to the global orientations of these NGOs, transcendent democratic movements have been able to spread internationally. In contrast, the PB has remained mostly within Brazil because the networks utilized were composed of mostly state and local community actors, so the supraterritorial connections were utilized to a lesser extent. Before proceeding to an explanation of the transcendent democratic processes involved in the participatory budget, it is important to keep in mind the caveat that the city of Porto Alegre already had a relatively dense network of community associations before community-building initiatives were undertaken. Despite this fact, many of these institutions were havens for vast amounts of patronage and clientelism40 , crippling their effectiveness.

It was in this environment in the late 1980s that the PB was initially implemented. Catalysts for shadow federalism, as in Mumbai, were present in Porto Alegre. The city witnessed an increase in poverty and inequality due to the downward spiral effect. The Brazilian federal government withdrew from its commitments to impoverished communities, essentially leaving the local governments to fend for themselves. Tax revenues, however, were lower than before so the local governments lacked the resources with which to improve their communities.41 A void of power and responsibility thus appeared as it did in Mumbai, paving the way for the PB to emerge in a manner consistent with the premises of shadow federalism, a joint effort of state and non-state actors to fill the de facto void in state authority. Although the initial change to the PB originated from the city government in 1988, it is not completely accurate to say that this initiative is simply another state-driven, state-enforced policy. The PT, responsive to the will of its working class constituents, was not in power before 1988 and was thus not an established state authority. It is thus perhaps more accurate to assert that this change in government was a response to the will of the people. Moreover, the PB is not simply a state-driven policy because the very survival of the PB depends on the engagement of impoverished and excluded citizens as well as the efforts of process leaders.

Therefore, a joint of effort among the state, local citizens, process leaders, and NGOs to increase depth was necessary to ensure the viability of the PB. In terms of the specific components of the PB, three categories for substantial improvement were identified: (1) concrete social improvement; (2) levels of popular mobilization; (3) new political relations with the state.42 These three areas for improvement were realized through the four spheres of the PB: (1) executive; (2) legislative; (3) civil society; (4) the participatory pyramid.43 These four spheres emphasize the joint efforts of state and non-state actors in implementing the PB. In the executive sphere, the mayor and the city departments are responsible for preparing the budgets. There are also budget area coordinators in this sphere who serve as community liaisons to maintain communication with local communities, an essential component of the deliberative aspect of transcendent democracy.44 In the legislative sphere, municipal legislators act to approve and amend the budget, and the civil society sphere consists of formal or informal neighborhood associations that advocate for funding for local projects.45 As for the participatory pyramid, it is “the hinge point between the executive and civil society.”46 This component has within it two subcomponents. The territorial subcomponent is made up of the micro-local, district, and municipal levels. Micro-local meetings are open to all members of the community with the purpose of discussing issues of importance to the community. These meetings are organized independent of the city government, and spokespersons are elected to present the results of deliberations to the district level of the PB, which organizes a list of priorities based on micro-local deliberations.47 The second subcomponent of the participatory pyramid is thematic, with deliberation classified by issue being carried out parallel to the municipal level of the territorial subcomponent. The top of the pyramid combines these two subcomponents, which send representatives to the municipal level to deliberate with other community leaders as well as members of the executive sphere, who are not allowed to vote. Meetings at the local community level to voice concerns are held in tandem, and it is important to note that at the municipal level, “participants do not just limit themselves to deciding on how the money is to be spent; they also discuss other budgetary issues (wages, operating procedures, etc.).”48

While some aspects of the PB may seem to mirror representative democracy, emphasis on the micro-local level has increased depth and galvanized more local participation and a greater sense of community. By early 2000 it was estimated that there were over 30,000 participants in the PB, yet despite this figure, it is still a relatively small fraction consisting of politically active members of impoverished communities.49 In comparison to a nearly ubiquitous absence of participation by the poor, this is still a promising sign. Diverse segments of the community, through meetings organized by process leaders, enhanced their political efficacy and sense of community, and began to more deeply embed themselves into the processes of contemporary globalization, evident via the hosting of the World Social Forum (the anti-Davos gathering) in 2001-2003 and 2005.

Governance in a Transcendent Network

The aspects of transcendent democracy evident in Mumbai and Porto Alegre have important implications for the future of sovereignty and governance. Many transcendent democratic initiatives are at work on relatively small scales and are greatly benefitting local communities. And so the question is how to expand the scope of transcendent democracies so that a fourth wave of democracy, drastically different from the first three, fully emerges. Due to the increasing interconnectivity in the globalized world, networks, both physical and metaphorical, have risen to prominence, and they play a key role in connecting these local instances of transcendent democracy and allowing a global wave of transcendent democracy to develop.

We have seen the principles of depth in action in both Mumbai and Porto Alegre. The network component of transcendent democracy can act to bring these local initiatives together into a fragmegrative system of holarchic governance. Every actor in a system is called a holon, and they are each “endowed with (their) own processing ability, (their) own autonomy and (their) own ‘mind’ or ‘intelligence’.” The holons together form a holarchy. According to Madron and Joplin, “taken to the next level, the…[holarchy] itself is a holon within…[a larger] holarchy. [This] is a model that offers unlimited scope for diversity, the framework for unlimited creativity.50

The case studies discussed exhibit the initial formations of network governance within the local sphere, with the pyramidal structure of the PB and the transoceanic linkages of SPARC. These cases are essentially micropoints of transcendent democracies—an enlightened speck within a vast array of problems in part caused by traditional forms of representative democracy. Supraterritorial networks of globalization are at work to forge a complementary system of holarchic networks to expand the transcendent democratic system to a regional and perhaps eventually global level. Processes of transcendent democracies are now at work in other countries like Azerbaijan. CHF International, an NGO, uses funding from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) to implement its Community Development Activity (CDA) program, whose goal is to increase “collaboration between citizens and local government, participation in local decision-making, and economic opportunities for citizens.”51 In addition to expanded networks promoting processes of depth, globalization has allowed transcendent democracies to begin to redefine the nature of sovereignty with the presence of shadow federalism and a decline in the monopoly of state control over local communities, which are ever more absorbent of people, goods, and ideas from other areas of the world. With transcendent democracies comes a better ability to combat global issues, such as poverty and climate change. While these issues are presently being addressed in local transcendent democratic initiatives, a network of transcendent governance allows for more effective solutions.

Visa International, led by Dee Hock, is one of the few examples of complex organizational systems currently in practice. It was designed to be “highly decentralized and highly collaborative,”52 much like transcendent democracies. Also, instead of imposing top-down governance, “the Visa bylaws encourage them [members] to compete and innovate as much as possible.”53 This method can be applied to governance because it takes into account the inherent complexities of world political, economic, and cultural systems. One-size-fits-all prescriptive solutions to global issues such as climate change have failed precisely because they view the world system through a reductionist lens consisting of states and their representatives. The United States, for instance, has not ratified the Kyoto Protocol because President Bush believes it has been unequally applied, with developing nations like China being exempt from the provisions of the treaty.54 Although the Kyoto Protocol has not been nearly as effective as it could be, a complex system of a network of transcendent democracies would allow for greater community input in the changes they would like to see and the environmental problems they are facing, thus increasing the likelihood for treaty ratification, compliance, and implementation of change. Efficient distribution of information across the network would provide greater access to facts about the issue, and the executive sphere (such as IGOs, perhaps playing a role similar to the PB executive sphere) would rely on the support of non-state actors and transcendent democracies to actively implement legislation based on deliberative discussion. The act of looking within, local introspection and community empowerment, fuses with looking beyond, the proliferation of transcendent democracies across the global system. While this utopia may seem to be an imagined distant future, the beginnings of it have started to foment. Increasing supraterritorial interconnectedness will make these networks more salient and perhaps catalyze a global emergence of transcendent democratic norms. Replacing the principles of continuous economic growth at all costs55 , be they social, political, cultural, or environmental, is critical for transcendent democracies to develop to their fullest potentials in this turbulent era. While the first three waves of democracy developed within a fluctuation between democracy and authoritarianism, the fourth wave emerges not out of a fluctuation, but out of a necessity to adapt to the complexities of contemporary world affairs.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Miles D. Townes and Chenkai Zhu for their insight and comments on previous drafts.

Endnotes

1. Huntington develops the idea of waves of democratization in The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 13-30.

2. For a cogent explanation of the effects of economic globalization on the role of the individual, see McKibben’s Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future (New York: Times Books, 2007).

3. Judith M. Greene, Deep Democracy: Community, Diversity, and Transformation (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999), v.

4. See James Rosenau, Distant Proximities: Dynamics Beyond Globalization (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003).

5. For a description of Earth as a complex system, see James Lovelock’s Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (Oxford University Press, 1987).

6. Robert D. Putnam, “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy 6:1, 73-74.

7. See James N. Rosenau, Distant Proximities, Ch. 18.

8. James N. Rosenau, Distant Proximities, 396-397.

9. Ibid., 397-398.

10. I am not, however, adopting an anti-statist viewpoint. Cooperation between governmental and non-governmental actors is of critical importance in a complex system of governance, as is evident in the Participatory Budget of Porto Alegre, Brazil.

11. Arjun Appadurai, Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger (Durham NC: Duke University Press), 94.

12. For a descriptive of intensity and other indicators of globalization, see David Held and Anthony McGrew, et al, Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, and Culture (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999).

13. Patricia A. Wilson, “Deep Democracy: The Inner Practice of Civic Engagement.” Fieldnotes: A Newsletter of the Shambhala Institute 3 (February 2004), 2.

14. Ibid., 3.

15. John Elster, Deliberative Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), qtd. in Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift, Cities: Reimagining the Urban. (Cambridge: Polity, 2002), 137.

16. Derek C. Malone France, “Process and Deliberation,” Process Studies 35:1, 110.

17. Ibid., 111.

18. Amin and Thrift, Cities: Reimagining the Urban, 138.

19. Rebecca Abers, Inventing Local Democracy: Grassroots Politics in Brazil (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2000), 5.

20. James N. Rosenau, People Count! Networked Individuals in Global Politics (Boulder, CO: Paradigm, 2007), 1.

21. Wilson, “Deep Democracy,” 2.

22. See, for instance, Bill McKibben, Deep Economy.

23. Amin and Thrift, Cities: Reimagining the Urban, 136-137.

24. Hans Skifter Andersen, Urban Sores: On the Interaction between Segregation, Urban Decay, and Deprived Neighbourhoods (Ashgate, 2003), 1.

25. For an explanation of the supraterritorial aspects of globalization, see Jan Aarte Scholte, Globalization: A Critical Introduction.

26. Eduardo Mendieta, “Invisible Cities: A Phenomenology of Globalization from Below.” City 5:1, 22.

27. Arjun Appadurai, “Deep Democracy: Urban Governmentality and the Horizon of Politics.” Environment and Urbanization 13:2 (October 2001), 27.

28. Ibid.

29. Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC), “Core Activities.” http://www.sparcindia.org.

30. Rosenau, Distant Proximities, 155.

31. SPARC, http://www.sparcindia.org.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Appadurai, “Deep Democracy,” 29.

35. Sheela Patel, “An Exchange with Kenya That Can Affect 10,000 Households.” SPARC. http://www.sparcindia.org.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid.

38. In Portuguese—Partido dos Trabalhadores, abbreviated as PT.

39. Marion Gret and Yves Sintomer, The Porto Alegre Experiment: Learning Lessons for Better Democracy (London: Zed Books, 2005), 1.

40. Iain Bruce, ed. The Porto Alegre Alternative: Direct Democracy in Action (Pluto Press, 2004), 39.

41. Ibid., 43.

42. Ibid.

43. Gret and Sintomer, The Porto Alegre Experiment, 26.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid., 31.

46. Ibid.

47. Ibid., 231-35.

48. Ibid., 35-36.

49. Bruce, ed. The Porto Alegre Alternative, 45, 133.

50. Madron and Jopling, Gaian Democracies, 123.

51. CHF International, “Developing Participatory Communities and Strengthening Economies.” http://www.chfinternational.org/node/27986.

52. M. Mitchell Waldrop, “The Trillion-Dollar Vision of Dee Hock,” Fast Company 5 (1996), 77.

53. Ibid.

54. The White House, “President Bush Discusses Global Climate Change.” June 11, 2001.

55. Mariko Frame and Haider A. Khan, Deep Democracy: A Political and Social Economy Approach (Tokyo: CIRJE, Faculty of Economics—University of Tokyo, 2007), 6.

References

Abers, Rebecca Neaera. Inventing Local Democracy: Grassroots Politics in Brazil (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2000).

Amin, Ash and Nigel Thrift. Cities: Reimagining the Urban (Cambridge: Polity, 2002).

Andersen, Hans Skifter. Urban Sores: On the Interaction between Segregation, Urban Decay, and Deprived Neighbourhoods (Ashgate, 2003).

Appadurai, Arjun. “Deep Democracy: Urban Governmentality and the Horizon of Politics.” Environment and Urbanization 13:2 (October 2001), 23-43.

Appadurai, Arjun. Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006).

Bruce, Iain, ed. The Porto Alegre Alternative: Direct Democracy in Action (Pluto Press, 2004).

CHF International, “Developing Participatory Communities and Strengthening Economies.” http://www.chfinternational.org/node/27986.

Frame, Mariko and Haider A. Khan. Deep Democracy: A Political and Social Economy Approach (Tokyo: CIRJE, Faculty of Economics—University of Tokyo, 2007), 1-22. http://www.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/cirje/research/dp/2007/2007cf469.pdf

Greene, Judith M. Deep Democracy: Community, Diversity, and Transformation (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999).

Gret, Marion and Yves Sintomer. The Porto Alegre Experiment: Learning Lessons for Better Democracy (London: Zed Books, 2005).

Madron, Roy and John Jopling. Gaian Democracies: Redefining Globalization & People Power (Green Books, 2003).

Malone-France, Derek C. “Process and Deliberation.” Process Studies 35:1, 108-133.

Mendieta, Eduardo. “Invisible Cities: A Phenomenology of Globalization from Below.” City 5:1, 7-26.

Patel, Sheela. “An Exchange with Kenya That Can Affect 10,000 Households.” Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres. http://www.sparcindia.org.

Putnam, Robert D. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy 6:1 (January 1995), 55-78.

Rosenau, James N. Distant Proximities: Dynamics Beyond Globalization (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003).

Rosenau, James N. People Count!: Networked Individuals in Global Politics (Boulder: Paradigm, 2008).

Waldrop, M. Mitchell. “The Trillion-Dollar Vision of Dee Hock,” Fast Company 5 (1996), 75-86.

The White House, “President Bush Discusses Global Climate Change.” June 11, 2001. http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2001/06/20010611-2.html.

Wilson, Patricia A. “Deep Democracy: The Inner Practice of Civic Engagement.” Fieldnotes: A Newsletter of the Shambhala Institute 3 (February 2004), 1-6.